📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

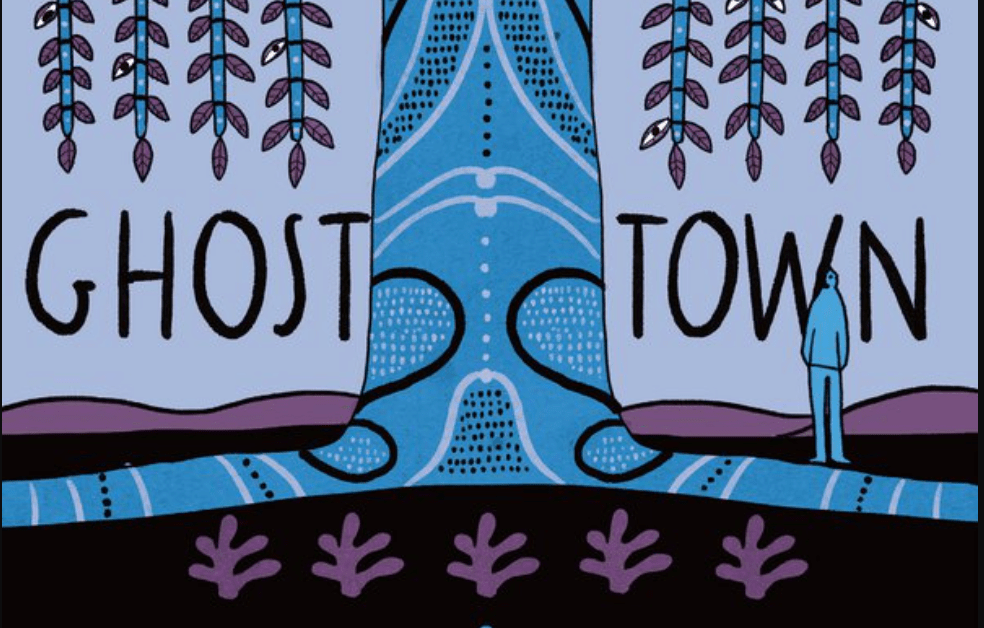

Kevin Chen (author) and Darryl Sterk (translator), Ghost Town, Europa Editions, 2022. 384 pgs.

Told from perspective of members of the Chen family, the plot and relationships in Kevin Chen’s novel Ghost Town is a game of logic that the reader slowly pieces together like a jigsaw puzzle. The family’s domestic dramas are entangled with Taiwan’s economic and social changes. In a modernised world that promises prosperity and global enlightenment, familial dysfunction and rural superstitions about ghosts do not disappear: they are merely replaced by equally arbitrary beliefs and silences about forgotten remote towns like Yongjing that fail to adapt to the country’s economic developments. Amid macro-scale changes, Ghost Town is an exploration of omissions—death, lost identities and stories—and the superstitions that rush in to fill the troubled void for everyday people.

The primacy of omission as one of the novel’s key themes is present from the beginning: Keith is reflecting on his boyfriend’s (only referred to as T) torrent of questions about Yongjing, Keith’s small hometown in Taiwan. By the end of this first vignette, Keith has already murdered T. Keith’s meta-fictive description of his made-up biography to T as “full of holes and contradictions, like a badly written novel” (p. 17) hints the insufficiency of mainstream narratives that privilege masculine dominance that excludes women and homosexuals.

Throughout the novel, women and gay men are consistently devalued and silenced. In a male-dominated culture, the perception of “having useless girls” (p. 28) shows in the image of Grandma discarding dogs “one by one… grab, toss, frown, grab, toss, frown” (p. 96). In contrast to the first Chen son Heath, the four sisters (Betty, Beverly, Belinda and Barbie) are denied meat and are given only tofu soup. Their mother’s feminising choice to also give Keith only tofu soup, like his sisters, suggests her implicit recognition and disapproval of his homosexuality. Early in the novel, male tyranny is evident in Barbie’s traumatic incident during which a man masturbates in front of her bedroom window until he ejaculates. The impression of the “shiny white [i.e., the novel’s motif for ghostliness] substance spurted onto the window” (p. 66) and Barbie’s consequent fear of sleeping near windows is a metaphor for the spectre of male entitlement that continues to cloud her marriage to the self-absorbed Baron Wang. Overwhelmed by the shadows of male sexual aggression, Yongjing is depicted as a hole of poverty and haunted primitivism forgotten in Taiwan’s economic acceleration.

Amid death and disorientation, superstitions rush in to fill people’s existential fears and need for cultural norms. These ghosts hold a more powerful hold on people’s perceptions on society than the living characters themselves. This shows in the first-person perspective used for Cliff (the Chen family’s dead father) and Plenty (Keith’s fifth sister, who died by suicide): Cliff and Plenty have the best view of their family’s realities and reveal most of the plot’s major mysteries (e.g., the release of a hippo at a private zoo, the circumstances surrounding their mother’s upbringing in a soy sauce factory-owning family). The persisting nicknames that residents assign to one another show how the myths perpetuated about people take on more life than the actual individuals themselves: for example, the fifth already-deceased sister Ciao is known by the nickname Plenty, in reference to men’s preoccupation with her breast size.

While modernisation promises to lift Yongjing out of its primitive superstitions, the characters merely find their country myths replaced by the mirage of global materialism and technology. The blurring of old town and modern superstitions first appears in the 21st vignette Snake Soup when Beverley is dutifully following a video tutorial on a spiritual ritual (“three clockwise circles above your head and three counter-clockwise circles in front of your best with the smoking paper” p. 167).

The design of White House, a successful brand of snacks and household products owned by Baron Wang represents the cult of consumerism that has replaced old town legends. The brand is an inescapable chant, appearing at every offering table and in places where the characters least want to encounter it. Its use of the colour white could refer to racial whiteness, alluding to the fatuous aspiration for Yongjing to become a “Paris of the Orient” (p. 109) or “New York of the East” (p. 109) and how White House’s architectural design is a “knockoff of the Palace of Versailles”(p. 181). Similarly, the beauty salon Paris Coiffure Workshop promises to sell an identity of French luxury. However, there is something deadening about being a European imitation, shown as the owner with “pale skin… floated across the floor” (p. 83) as a contrast to the “earthy” country folk. The colour white is a motif used to code characters who have become ghostly in some way (e.g., Keith’s complexion after he has left prison, the already deceased T, the shadowy exhibitionist’s semen against the window which drives Barbie’s fear of windows).

As was the case in Yongjing, the proliferation of superstitions signals a modern world that is rife with omissions and crucial silences in the form of media misinformation and partial truths. In the fourth vignette, Household Registrar Chen, Betty struggles with cameras “always [being] in your face” (p. 58) and the fact that “anyone could start recording at a moment’s notice” (p. 38). Social media’s capacity to extract a person’s false likeness and make it even more prominent the actual individual shows when Betty is framed as discriminatory towards guide dogs, unleashing the internet’s fury against her. As the false image of her grips people’s imaginations, Betty feels herself become “colourless… like a ghost… automatically edited out of people’s vision and hearing” (p. 43). Similarly, the full political and social picture surrounding Keith’s murder of T is never explored in the media.

However, solidarity among social pariahs appears to be the sole cure to the ghosts and superstitions persisting through both Yongjing and the modern landscape. In defiance of a world that tries to silence women, the four unwanted Chen sisters display the full breadth of their outgoing characters’ when they are together: “normally the sisters’ conversations were dull, but as soon as they stepped onto the verbal battlefield, swords came unsheathed and arrows snapped into strings. Like theatre actors, they didn’t need microphones to project their voices (p. 269).” In the women’s quieter moments, their concerned letters to Keith and anticipation of his return from prison illustrate an appreciation of his poetic character, overcoming society’s disgust towards his homosexuality. Even beyond Keith and his four sisters, readers glimpse moments when marginalised characters advocate for one another. As early as the 11th vignette, Pare a Pear, the dog (Blackie) that Betty cares for tries to protect her from Grandma’s beating. The 32nd vignette, I’m Just Here to Practice My Routine, describes how Keith’s stripper classmate rescues him from a homophobic attack.

A deeper exploration of these alliances among social pariahs would have enhanced the reading experience. These relationships were the only effective counterbalances to the novel’s depictions of masculine violence and sexual aggression which occasionally seemed gratuitous. Furthermore, too much of the plot and character revelations occur in the last quarter of the book, while the first three quarters are mired in somewhat repetitive flashbacks and backstory. The vignettes are often short and switch rapidly among the characters: this is not ideal because every time a new vignette starts, the story’s momentum plummets as the reader must reorient themselves, trying to work out the vignette’s central character and location. At the same time, I realise that the dynamic sequence of vignettes suitably mimics the characters’ alienation from one another and wider society. Perhaps my criticism about the rapidly switching points of view is merely personal preference.

Some reviews have described Ghost Town as a gay bildungsroman intertwined with a murder mystery. Others have tried to liken the author to Keith. However, such an overemphasis on the author’s personal self or one character’s social label misses the novel’s broader point: Ghost Town is a profound and ambitious story about the trauma-induced silences and unshakable human instinct to fill voids with superstitions.

How to cite: An, Frances. “Omission and Superstition in Kevin Chen’s Ghost Town.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 18 Oct. 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/10/18/ghost-town/.

Frances An is a Vietnamese-Australian fiction and non-fiction writer based in Perth. She is interested in the literatures of Communism, moral self-perception, white-collar misconduct and Nhạc Vàng (Yellow/Gold Music). She has performed/published in the Sydney Review Of Books, Seizure Online, Cincinnati Review, Sydney Writers Festival, Star 82, among other venues. She received a Create NSW Early Career Writers Grant 2018, partial scholarship to attend the Disquiet Literary Program 2019, and 2020 Inner City Residency (Perth, Australia). She is completing a PhD in Psychology at the University Of Western Australia on motivations behind “curbstoning” (data falsification in market research). [All contributions by Frances An.]