📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

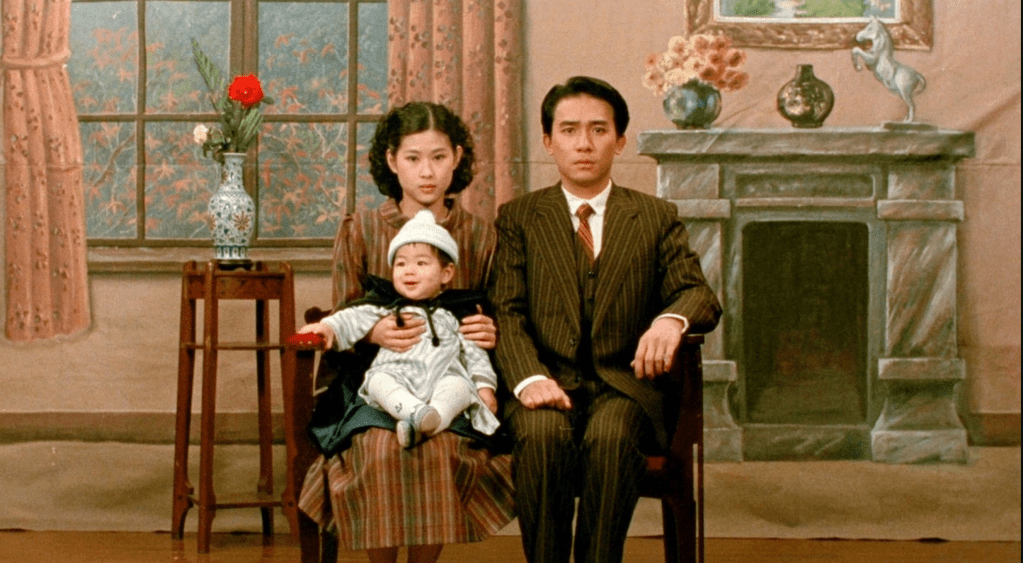

Hou Hsiao-hsien (director), A City of Sadness, 1989. 157 min.

Since its release in 1989, the epic proportions of A City of Sadness have transcended its story by becoming a time capsule into the past and look into the future. The tagline in the film’s trailer initially caught my attention: “A must-see movie for all Taiwanese.” I’m not Taiwanese, but the 4K digital restoration of A City of Sadness has been playing in select cinemas in Hong Kong for months now. The film was pleading to be seen. I could not ignore the cry any longer.

Directed by Taiwanese film master Hou Hsiao-hsien, A City of Sadness presents a portrait of the Lin family in Taiwan in the late 1940s following the end of World War II, during a period in Taiwan’s history known as the “White Terror”. The end of Japanese colonial rule in Taiwan was followed by the oppression of Taiwanese people by the authoritarian Republic of China Kuomintang government, and resulted in the mass execution, murder, and imprisonment of civilians opposing Kuomintang rule. As the eldest Lin brother, Wen-heung, puts it plainly: “They make the laws and they change the laws. How pitiful we are, living on this island. First the Japanese, now the Chinese. They all exploit us and no one gives a damn.”

The film opens with Wen-heung awaiting the birth of his child while the Emperor of Japan announces the country’s surrender on the radio. Throughout the film, Hou melds domestic scenes together with large-scale geopolitical developments. Dissonance is created between the subjective present moment and the engulfing weight of history unfolding. By keeping key players and policy makers of history to voices on the radio and depicting only the faceless effects of their choices on the lives of everyday people, Hou creates an intimate yet jarring atmosphere, and suggests that the events occurring in the family living room carry more weight than the actions of emperors, presidents and generalissimos. Wen-heung, in his current time and space, holds his baby in his arms for the first time.

Hong Kong actor Tony Leung Chiu-Wai plays Wen-ching, the youngest of the Lin brothers, who lost his hearing as a child and spends his days tinkering with his camera and developing film in his photography studio. He communicates primarily by writing on his notepad, especially with Hiromi, a nurse at their local hospital and sister of Wen-ching’s close friend Hiroe. Without speaking, Wen-ching uses his body language and keen eye to frame subjects in his photography, bringing attention to the importance of what is inside and outside the frame.

The film contains beautiful sweeping landscapes of Taiwan’s countryside, images of the warm, soft glow of Jiufen village, and the ornate ancestral home of the Lin family. As terror encroaches on the Lin brothers’ lives, the audience is swallowed by the wideness of the frame and surrounding environment in the film’s most striking scenes. When the Lin family’s third brother, Wen-leung, is chased and beaten, the extreme wide angle frames the village shops and stalls more than the beating. A few scenes later, a lion dance performance and celebration is held in the same space. Violence is depicted with distance but not detachment. The distance of the camera and the stretch of time passing from the violence, does not dull the pain of it.

The unrelenting frame makes the audience witness to destruction, but despite this, life continues to persist. For every scene of political persecution, violent arrest, and death and despair, the film reminds us of life by presenting lengthy scenes of humanity—children playing in a community opera performance, men singing folk songs after eating hot pot, and a couple seeking blessings on their wedding day. The film never loses sight of people and we cannot, and must not, look away.

How to cite: Wong, Natalie. “Pain and Persisting: Hou Hsiao-hsien’s A City of Sadness.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 5 Oct. 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/10/05/sadness.

Natalie Wong is a writer from Hong Kong. She is a graduate of the University of Southern California’s Writing for Screen and Television program and has experience developing original TV projects in Asia and the US. Her fascination with outsiders is why she writes about people trying to find happiness in worlds that do not allow it. Recently, her feature screenplay Gor Gor was recognised as a quarter-finalist by the 2023 Academy Nicholl Fellowships in Screenwriting. Natalie is a member of Hong Kong Women in Publishing Society and runs the blog You Make Me Sik about food she doesn’t like.