📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

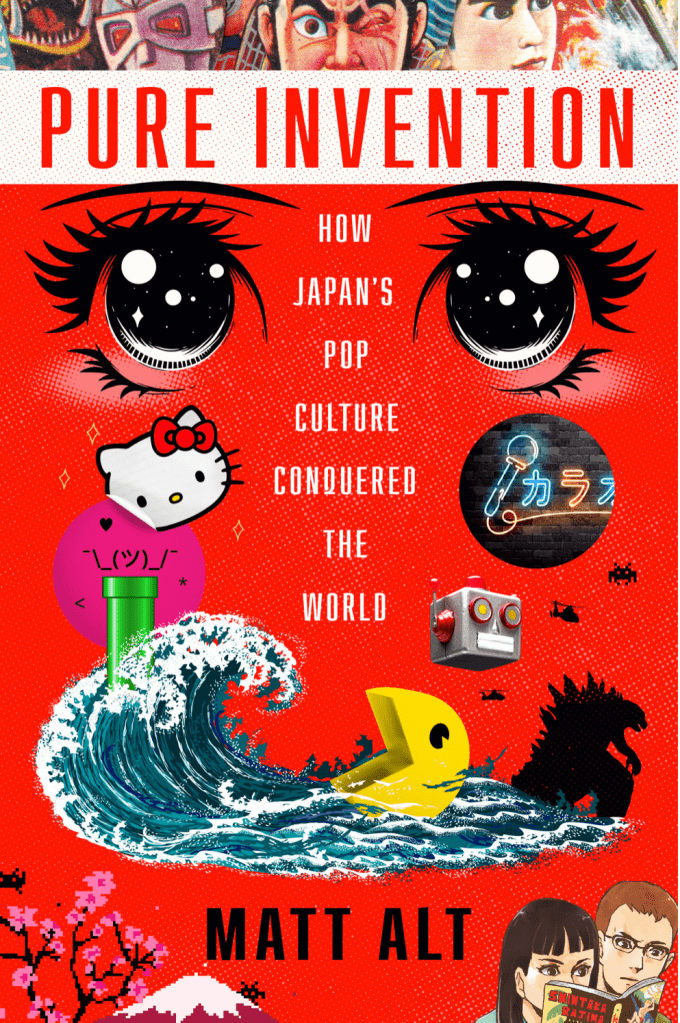

Matt Alt, Pure Invention: How Japan’s Pop Culture Conquered the World, Crown Publishing, 2020. 384 pages.

The subtitle of the book is enough to entice anyone browsing a bookstore who is half-interested in Japan to grab a copy off the shelf and flick through the pages. The hardcover edition features world-famous images of 20th-century Japan: big manga eyes, Hello Kitty, a neon karaoke sign, Pac Man, and the shrug emoticon.

Even if you know the answer to “How Japan’s pop culture conquered the world”, you will be interested in knowing more. Why manga, instead of French-Belgian comics? Why is karaoke culture different in Asia and the United States? Why are Pac-Man and Godzilla still recognisable worldwide, even for people who never encounter them at first hand?

Japan’s pop culture is noticeable when you step outside. Sony’s PlayStation and Nintendo remain the bywords for video games. Uniqlo and Netflix cash in on anime licenses. Older people will remember the dominance of Japanese electronics and tech up to 2010, before they were surpassed by American, Chinese, and Korean successors. For many, Japanese appliances and cars remain the primary choices.

So how does Matt Alt, another American writer, translator, and reporter in Tokyo, define “pop culture”? Why does this book cover the Sony Walkman, but not the Toyota Corolla? And despite the title, why doesn’t this book cover Japanese rock and pop?

Alt states that he’s interested in examining the histories of fantasy-delivery devices, and these devices must satisfy three criteria: inessential, inescapable, and influential. These criteria put a Toyota car and a Sony VCR out of the book’s purview. A Toyota car is essential, and a Sony VCR is not influential in changing your perception of Japan.

These fantasy-delivery devices were always initially designed for Japanese consumers. They offered not only entertainment but also escapism, and past Western visitors of Japan noticed it as a dreamland, where adult men and women enjoyed every entertainment in the field and in the tea house. Even when Japan sank into melancholy and pessimism after 1990, their fantasies spread throughout the world thanks to globalisation and digitalisation.

Alt reminds us that while these aspects of pop culture elevate Japan’s image worldwide, the creators are hardly national heroes in Japan. These artists and inventors are rebels and outsiders, men and women who are not role models for Japanese parents and authorities.

The Rise: 1945–1989

Like other stories of modern Japan, we start with the aftermath of the Second World War. Japanese children saw American soldiers zooming past a charred Tokyo on their jeeps and hoping to be given chocolate bars by them, while the Americans were surprised to find a sophisticated land of origami, bento, and gentle people. The Japanese are sophisticated because the peasants and merchants had to follow the exquisite tastes of the samurai and kept that tradition after the abolition of feudalism. Arguably the inventor of the department store, with Mitsukoshi and Matsuzakaya established in the 17th century, Japan has for centuries mastered the art of consumer packaging, the key to its cultural export.

Japanese crafting is not easily replicated, as the artisans study like martial artists, with decades of rote practice, hierarchy, and discipline. And yet they are also playful people, a duality that keeps intriguing foreign observers.

American and European toy manufacturers had already complained about Japanese imports before the war, and Japanese tin and paper toys returned to Western markets in the 1950s, ironically including models of American war machines. When American boys and their fathers wanted suburban cars instead of jeeps and bombers, Japan quickly provided them with miniature Cadillacs and Buicks, burying the British and German toy industries in just a decade. But the low costs of Japanese industry meant the workers lived on the poverty line, and labour activism and anti-Americanism defined Japan in the 1950s.

The 1960s brought in the dreams of space and robots, as Tokyo was rebuilt as a futuristic city for the 1964 Summer Olympics. The baby boomers watched the first anime, Mighty Atom, an adaptation of Osamu Tezuka’s comics. More than a mere children’s show, Mighty Atom discussed citizenship and discrimination. Still, Tezuka was denounced as a sell-out by his fellow artists, who created underground adult comics known as gekiga.

The late 1960s counterculture also hit Japan and Mighty Atom gave way to gekiga. These comics and cans of beer were more affordable for Tokyo workers than their dreams of colour TVs, refrigerators, and cars. The boomers also hit a breaking point as overcrowded schools and universities had become industrial pipelines to corporations.

Opposition to the Vietnam War led to the radicalisation of the Zengakuren—the association of left-wing students. American and British boomers had Joan Baez and The Beatles, while the Zengakuren had gekiga. Both Mighty Atom and Tomorrow’s Joe, a fictional slum boy aiming to become Japan’s best boxer, became the icons of resistance. It all burned down in the 1970s as some graduates became Red Army terrorists, and Tezuka’s Mushi Production, which produced Mighty Atom and Tomorrow’s Joe, went bankrupt in 1973 (the current company is established in 1977).

But overall, the 1970s was kinder to Japan than to the West. The karaoke machine, while killing house bands, energised pubs and salarymen who became indoor pop stars after a hard day’s work. Girls and women had their own manga and built their fandom subcultures of fanzines, imagined homosexual romances, and frank discussions on sex and politics. They also had Sanrio accessories, which popularized the concept of kawaii cuteness.

By the 1980s, Japan had become a leader of the global economy and technology. Sony, which had decades of experience building compact transistor radios, modified the Pressman voice recorder and created a light headphone set that weighed just 50 grams. The Sony Walkman began its life in the West as a vanity device for rich men listening to jazz or classical music, before younger writers like William Gibson experienced how walking while listening to rock changed one’s perception of the city. If karaoke made you the star of the bar, the Walkman made you the star of the city.

America then got nervous about Japan buying everything in the country up, and the cyberpunk genre exploits this worry—cruel Japanese corporations treat American dads like salarymen, while the American city is turned into a neon-lit Hong Kong-like slum. Japan seemed unstoppable until coincidentally, the Lost Decades began in 1990.

The Fall: 1990—the 2000s

Like other books on modern Japan, Alt’s cannot pinpoint precisely the sudden crash of the Japanese economy. The salarymen fell and replacing them as the vanguards of new technologies were teenage girls. Yuko Yamaguchi, who shaped Hello Kitty into a world-famous character, talked to young women visiting Sanrio Gift Gate stores and took notes of their fashion, slang, and aspirations.

Karaoke lounges, formerly the haunts of salarymen, were taken over by teenagers, just in time for the introduction of the more private karaoke boxes and streaming videos, which also collected data on popularity and preferences. Avex Trax, a leading J-pop label, issued singles for karaoke instead of radio, and the home karaoke box’s popularity led to higher CD sales.

The girls also communicated with pagers, thought of as a boring business-like device in the West. They created their own codes using phonetic readings of numbers, and when the mobile phone became affordable, they played around with emojis, 25 years before the rest of us.

Unfortunately, while the girls were known as gyaru (gals) and then kogal (teenage gals or cool gals), the boys came to be known as otaku, an archaic nerdy term for “you”, like “thee”. Anime might have become popular, but it had also become edgier and gloomier, especially as VCRs enabled producers to directly sell their works to consumers, bypassing TV censors. In other words, the girls escaped to the city while the boys escaped to their TV sets.

But you could guess which one of anime or the emoji became popular first in America. Anime video were no longer Chinatown bootlegs, but a prestige import lauded by rich geeks from both Silicon Valley and Manhattan. Anime reached the height of its popularity in America in 2003 as Spirited Away won an Oscar, Kill Bill: Volume 1 included an anime sequence, and the Animatrix featured anime short films to accompany the Matrix trilogy. The fame didn’t last long. At least anime had its moment in America, unlike Japanese pop, which has never succeeded outside Asia.

Alt ends his pop culture history with the anonymous online forums of the 2000s, and here sadly the book strays from its scope. The story of 2channel is as compelling as other objects. Starting off as a general forum for otaku, it gamed the Time Magazine’s Person of the Year voting in 2001 and offered a national hope with the story of the Train Man who found love in February 2004, before it turned into a cauldron of ultranationalism following the economic and cultural rises of China and South Korea in the late 2000s.

Here Alt turns his attention to America. Christopher Poole created the American copy of 2channel, 4chan, which also evolved from a porn and otaku board into activism against Scientology before degenerating into a far-right forum in the 2010s.

I understand the intention of Alt to describe the genealogy of 4chan and its influence on American politics, but in effect it makes the final part of this book about United States, not Japan. And unfortunately, the story doesn’t return to Japan.

Endless Dream

The 2010s serves only as the epilogue here, which discusses Haruki Murakami’s Dance Dance Dance, published in 1988. I had the high hope of learning about Japan after 2010, but this book is not about it. Japan didn’t create fantasy devices in the 2010s, but I could think of two post-2010 phenomena that fit into Alt’s criteria of inessential, inescapable, and influential.

The first is the revival of city pop, a 1980s genre designed for car stereos and the Walkman. American hobbyists created the vaporware genre in the early 2010s by manipulating funk and disco songs and used 1980s Japanese imageries, both anime arts and commercial clips, as visualisers. The subculture renewed online interest in city pop, the sound of prosperous Japan, and by the late 2010s, both K-pop groups and independent Japanese producers had released new city pop songs.

The second is the minimalist home management exemplified by Marie Kondo, who gets a name check in the epilogue. After finding fame in Japan in the early 2010s, Kondo had her book published in United States in 2014, and she became the most famous Japanese person of the Twitter and Netflix era. At first, she was disliked by Western conservatives for bringing Japanese discipline and spirituality to Western homes, before she also fell out of favour by progressives for the very same ethics, as the trend for minimalism and self-discipline waned in the 2020s.

Oscar Wilde sounds too harsh, if not racist, when he described Japan as a pure invention in his 1881 essay “The Decay of Living”. Japan exists, and as he wrote, is a stylish and artful place. Japan remains the ideal nation for most other Asian societies. It remains the most popular tourist destination. It remains a canvas onto which to project our dreams of safety and tidiness, and our dread of apathy and loneliness. Pure Invention has everything you want to dive into Japan’s 20th century pop culture, but another book covering the 21st century is still out there, waiting to be written.

How to cite: Rustan, Mario. “We’re All Dreaming of Japan: Matt Alt’s How Japan’s Pop Culture Conquered the World.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 6 Sept 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/09/06/dreaming-of-japan.

Mario Rustan is a writer and reviewer living in Bandung, Indonesia. [All contributions by Mario Rustan.]