📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

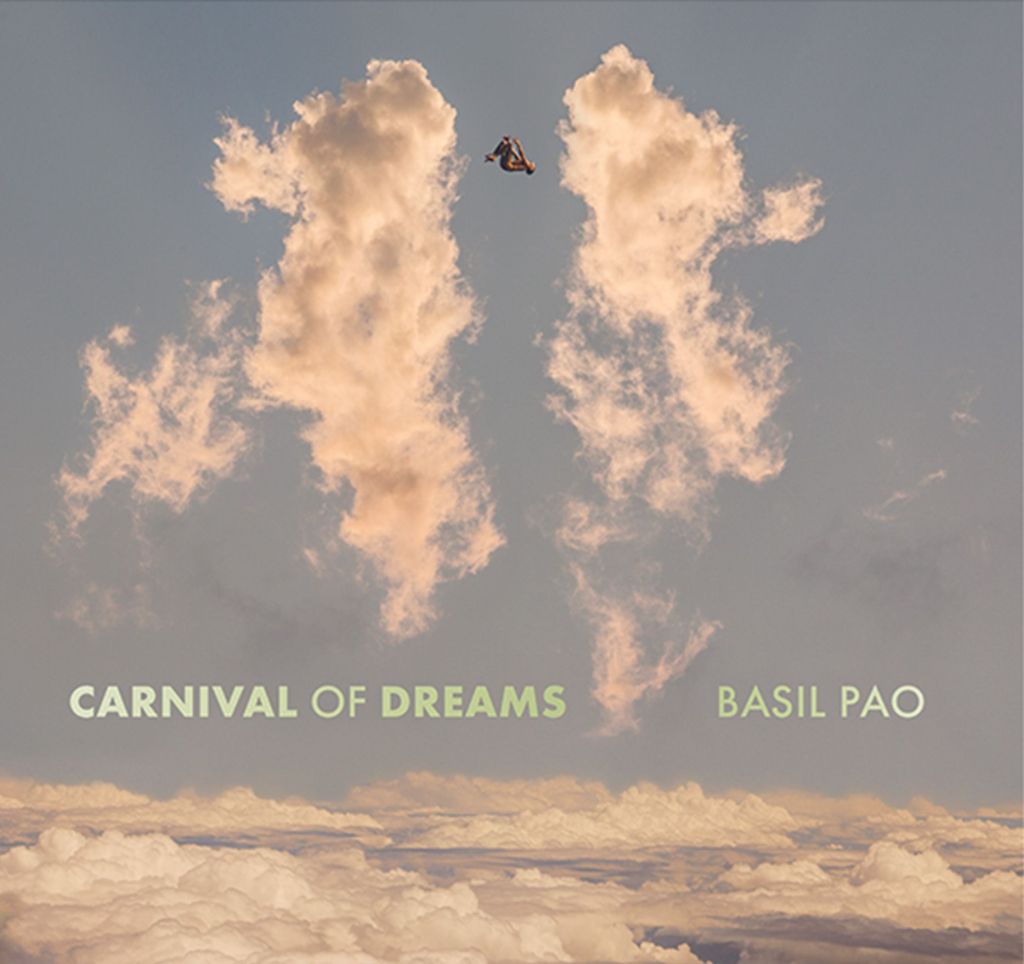

Basil Pao (photographer), Carnival of Dreams, with an introduction by Pico Iyer, Hong Kong University Press, 2023. 208 pgs.

Huge cubes float in the air, painted with different images on each side. Above the clouds, we see René Magritte’s iconic painting The Son of Man, the cover of George Harrison’s album Somewhere in England, and one of Andy Warhol’s red lip prints. Human figures, in dark silhouette, are walking on the top of the cube. An aerial view of a green landscape appears far beneath the cubes. The clouds fill the gap between foreground and background, the atmospheric layer and the distant earth. Thanks to the realistic texture of the clouds, the depth of field is widened, rendering the photomontage not only a flattened collage but a three-dimensional aporia. This is one of the opening images of Hong Kong artist and photographer Basil Pao’s photo book Carnival of Dreams.

The title of the book evokes a familiar history of photomontage, an image-making practice that rose in stature in the early twentieth century. Coinciding with the psychoanalytic rediscovery of dreamscapes—a realm that unsettles the conscious mind, photomontage embodies the desire of the modernist cultural milieu to disturb the habituated regime of perception. While the technique of cutting, pasting, and assembling images appeared as early as in the nineteenth century and was initially a vernacular mode of image production that can be found in mainstream print press and commercials, the historical avant-gardes mobilised the technique and inaugurated photomontage as a radical breakaway from realist modes of representation.

Surrealists, Dadaists, and Futurists extended the technique into painting, photography, and design. During the interwar era, photomontage developed into a prominent form of social critique. Artists such as Hannah Höch and John Heartfield extensively used stock images from the mainstream press. By assembling images into fragmented and oftentimes illogical collage, early practitioners of photomontage aimed to create a defamiliarising effect that questioned the mass production and reception of images.

Viewed in today’s hyper-mediated digital world, the technique of photomontage is, to some extent, basic and omnipresent. One can generate photomontages or collages by using Photoshop or smartphone apps. What distinguishes photomontage from other artistic representations—namely, a new way of capture reality, now became the dominant mode of processing the lived condition. Image production and the capture of the real does not rely on mimesis but on the infinite fragmentation and reassembling of the “raw material”. However, precisely because of this, Carnival of Dreams appears strangely nostalgic.

A work that compiles Basil Pao’s photomontage design and photography works from the 1970s to the recent years, Carnival of Dreams presents a detailed account on the evolving history of photomontage and the specific materiality of the craft. Back in 1977, “cutting” was not yet a keyboard shortcut. Basil Pao, already a prominent designer, started to use an X-Acto knife to experiment with found images in magazines and books. Imitating David Hockney, Pao created a series of works, among them album covers for the renowned Hong Kong singer and music producer George Lam, whose entry into the music scene is considered a watershed moment of the Cantopop industry. In addition, Pao also created the album cover for Panamanian-American drummer Billy Cobham’s 1974 Crosswinds and George Harrison’s 1980 Somewhere in England.

Pao recalls that back then, he had to travel to Japan to use one of only two high-resolution photo compositing machines in the Asia-Pacific region to produce photomontages. The other machine was in Australia. “The same computing power that then resided within a machine occupying a rather large room in an industrial building on the outskirts of Tokyo,” Pao writes, “is now routinely available in most professional laptops.” (21) Like many industrial shifts, the once-upon-a-time transnational connectivity formed in the process of image production is now transformed into a different process that seems attainable yet more invisible. And photomontage seems to have foreseen the collapse of space and time by offering a distinct materiality of the near and the far.

In such a way, Pao’s technique of photomontage, or any practice of cutting, pasting, assembling images is neither old nor new. Photomontage can be seen as a snapshot, a materialised form of the exchange and moreover, the exchangeability ad infinitum, among materiality, abstractised image (data is one form), and our sensory capacity. Does the exchange evoke a passive, contemplative sense of relationality in the age of global image economy, or a dissensus that proliferates fissures and differences during our encounter with the images? Rather than forming a determinant answer, it is productive to dwell with the photos. How does the dreamlike world manifest?

First, we have the play of signs. A tortoise crawling on a highway. A Black man walking in the deserted landscape sandwiching the road. Cosmological imagery fills the tortoise body, and on the top of its hard shell lies the tip of an iceberg. The tortoise is a shape, a frame, more a bio-cosmological complex than an entity. Conflicts are usual tropes to destabilise the perceptual consistency. We see a pilgrimage on a cutting board. Land becomes sky while clouds substitute for river. There are intermeshing cultural symbols, from Superman flying across the sky on a day when a huge crowd gathers at Tiananmen Square, to a jet flying over the transitional Chinese Shan Shui landscape. Aside from the immediately recognisable interplay, we find the manipulation of scale. In one beautifully designed image, massive goldfish, larger than humans, fill the river, their red skin glittering in the dusk. Cosmological images frequently appear: we see mercury ascending. Surrounding the planet, birds are flying past the yin-yang symbol. And of course, there is photography’s perpetual obsession with the invisible: a meditating man, whose chakra emanates from his reflected image on the river. What is most interesting is the juxtaposition of different perspectives. In one of the last images, a man is standing on top of a hill, looking far into the distance. The upper part of the image consists of a far-off river. A boat drives by, leaving ripples on the water surface. The river and boat, however, are presented as if the viewer is adopting a bird’s-eye view, while the man on the hill is presented in a way that the camera is directly behind him. The image incorporates both human perspective and a bird’s-eye, machine-like view.

The varied forms of defamiliarisation is playful in its nature. However, rather than redistributing the established habitus of viewing images, what we have in this refined art book seems to be an accumulation of feedback that works on an ever more rapid scale. The visual citation and fusing are spectacular precisely because of how fast the symbols and meaning can be quickly evoked in one image: Andy Warhol, geometry, religion, East-West cultural clash. As a result, the “carnival of dream” became a palette of tokens, signs, and a pastiche of information that naturally reminds one of the age of AI, when image and language are engineered into stable feedback loops, when symbols, carrying the mystic dream, gained a new shade of meaning.

Carnival of Dreams traces Pao’s journey from using a surgery knife, modernity’s favorite metaphor of avant-garde aesthetic, to the mastery of digital tools that also made photomontage easily accessible for all. It is not surprising that Pao, as a photographer whose practice weaves together varied forms of image-making—commercial, documentary, mainstream, and independent—pays special homage to Belgium surrealist artist René Magritte, who also works across commercial and independent venues. One section of Carnival of Dreams composes of Pao’s remakes of artworks by Magritte, including Les Amants (1928), La Voix des airs (1931), La Durée poignardée, Le Principe du plasir (1960). Painting the familiar in an unfamiliar way, Magritte certainly fits in the modernist tradition. In Magritte’s age, technical reproducibility, wrought by industrial capitalism, has already been symbiotic with the passionate dive into the most esoteric dream. I find it both curious and thought-provoking that in today’s age when technology’s extensive dispossessing force constantly brings images, resources, and culture from afar to close at hand, for Pao, photomontage still inheres the aura of dream, a language that is also an interface which facilitates the generation of unfamiliar sensations.

My curiosity is entirely neutral and sincere. For I see in Pao’s digital X-Acto the reverberation of the sweeping fascination with metaphysics, spirituality, and cosmology in today’s cultural milieu. Art and technology, science and mysticism, the liberation of body and the continued militarisation of a central nervous system—everything everywhere all at once. How to make sense of it? A continued colonisation of difference? An animistic obsession with the nonhuman as a spectacle or a form of critique? A shifting mode of resistance when our bodily sensations and our daily immersion in sounds and images have already become a part of the digital infrastructure?

As I slip through the playful beautiful book, Pao, after conjuring many things in his writing—aboriginal Australian mythology, ancient Eurasian culture, to name but a few—responds to my thoughts without answering any of the questions: “Looking back, it has been a mind-twisting rollercoaster ride from the Age of Aquarius’s consciousness-expanding substances to the Digital Age of zeros and ones when one can receive images in the comfort of home from a distant galaxy 220 million light years away via man-made machines.”

Maybe, in the end, what matters is still the question. How do we make sense of dream? Its desire, coding, and creativity? As I try to escape from any burden of conclusion, I can only think of the language of André Breton, the “pope of surrealism”, who once declared, in a manifesto, that dreams are “Beyond Good and Evil”.

How to cite: Chen, Junnan. “Digital X-Acto: Basil Pao’s Photography Book Carnival of Dreams.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 5 Sept. 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/09/06/carnival.

Born and raised in Shanghai, Junnan Chen is a PhD candidate at Princeton University, pursuing a joint degree in East Asian Studies and Interdisciplinary Humanities Studies. Before Princeton, she gained her BFA degree from New York University Tisch School of the Arts, focusing on filmmaking and creative writing. She is a thinker and practitioner of both analogue and digital image-making. Her writing and film work explore the themes of time, gender, and visual technology. [All contributions by Junnan Chen.]