📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

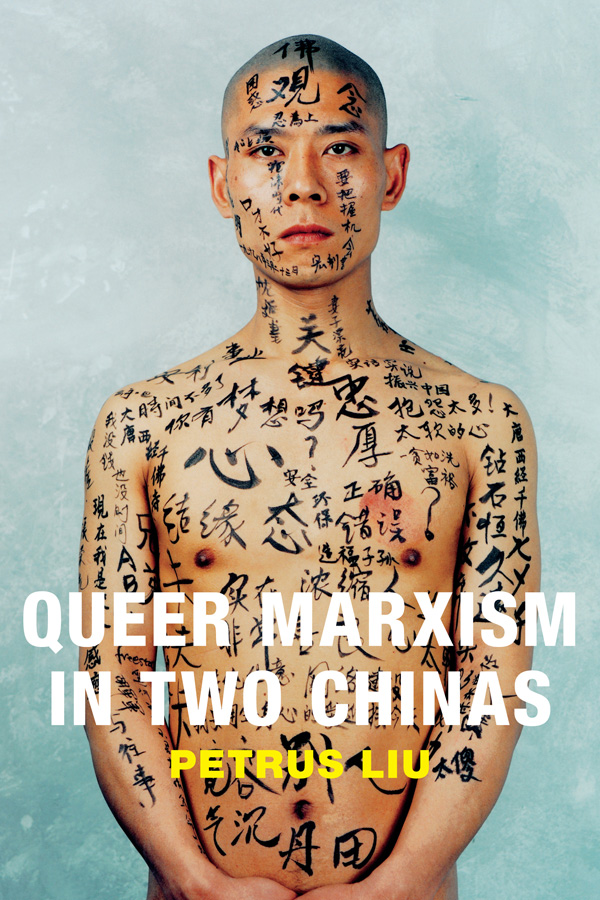

Petrus Liu, Queer Marxism in Two Chinas, Duke University Press, 2015. 256 pgs.

Recent scholarship on the flows of desire and subject formation in China has seemingly operated with the idea that a fundamental shift in attitudes—both governmental and social—towards queerness took place after Deng Xiaoping’s reforms. They have emphasised the agency of queer desire against state prescriptions, while also suggesting that new sexual politics may inhere in new forms of advanced liberalism. In that perspective, Marxism and queer theory stand outside of each other, and it is precisely a turn towards neoliberalism and post-socialism and that has enabled a queer culture to emerge in the PRC. The emergent Chinese queer subject mimics its Western counterpart, and seeks inclusion in society through the learning, embodying, and reproducing of normalised behaviour to demonstrate that gays and lesbians are too morally upstanding citizens. In this “homonormative turn” where China’s neoliberal integration into global flows of capital accompanies gay normalisation, “queerness” is couched in the signifier of identity, and the fight for “queer rights” becomes a mark of linear civilisational progress.

Petrus Liu’s Queer Marxism in Two Chinas challenges this narrative, shedding light on a vibrant tradition of queer thinkers and artists that have creatively engaged with Marxism, both in post-socialist China and anti-communist Taiwan. Taking Marxism as a methodology for reading the impersonal, structural, and systemic workings of power, Chinese queer Marxists develop an arsenal of conceptual tools for reading the complex and overdetermined relations between human sexual freedom and the ideological cartography of the cold war. This Chinese queer theory, Liu proposes, poses an alternative and a challenge to US-based queer theory. The urgency of this challenge, for him, is twofold. First, US-based queer theory is restricted by the exploration of the intersectionality of identity categories in a pluralist liberal culture. Second, and relatedly, acknowledging the contribution (and contingency) of Chinese queer Marxism disrupts a linear view of queerness and queer liberation that sees the developments in China as the retreading of a path first delineated by the United States.

This definition places Queer Marxism in Two Chinas as a work of social theory itself, in the Marxist tradition. Liu acknowledges that fact: rather than “queering Marxism” through new conceptual frameworks, he is primarily preoccupied with bringing Marxism to bear on queer lives on both sides of the Taiwan Strait. This strategic deployment of a materialist methodology enables Liu to propose queerness itself as a global discourse that is the product of historically determinate circumstances. That is to say, queer theory as thought, knowledge and ideology (or “discourse”) only emerges insofar as it is the producer and product of politico-economic arrangements. Thus, while the Stonewall riots are seen as a watershed moment of queer liberation (particularly so in the US context), he proposes that a different event played a central role in the development of Chinese queer thought: the 1949 division of China into the PRC and the ROC. The geopolitical tensions between the two Chinas are more than the background for the creative interventions of Chinese queer Marxists. They are the by-product of unfinished Cold War projects, that these artists and theorists seek to diagnose, describe and speak against.

Structuralist in its approach, Chinese queer thought sees queerness as that which attaches itself to differently positioned subjects within a social field after the deployment of a set of politico-economic and sexual distinctions. For that reason, queerness comes to encompass all of those who exist marginally within the intertwined landscapes of class, gender, sex and sexuality, and power.

An example is the main character of Xiao Sa’s novel Song of Dreams, Yu Zhen, a woman who rises from humble beginnings to become the president of a housing development corporation during the Taiwanese economic miracle. The story of Yu Zhen intertwines the boom years with her personal journey as woman, and her personal trajectory of economic success as a self-reliant urbanite is underscored by a dynamic movement whereby she moves away from a heteronormative model of human intimacy. She begins the story as a provincial teenager in a dysfunctional marriage with Huang, whom she leaves behind for Allen, an American soldier stationed in Taiwan during the Cold War. With her newly expanded horizon where the United States represents not only “romance” but economic prosperity made palpable through an influx of commodities and a luxurious lifestyle, Yu Zhen learns how to perform neoliberal and cosmopolitan womanhood in Taipei’s fast-changing environment. In this environment she meets Liu, an older man who enters into a business venture and extramarital affair with her, mentoring her in the cultural codes of the bourgeoisie. After she becomes a successful businesswoman in her own right, she takes on the younger and beautiful but vapid Luo, whom she supports financially. The novel closes with Yu Zhen acquiring all the power and wealth she wanted as a child, while longing for the human connectedness she once enjoyed before the Taiwanese economic miracle transformed life beyond recognition.

Through Song of Dreams, Xiao Sa performs an analysis and critique of Taiwan’s economic miracle and its impacts on human relations. Yu Zhen’s story is told through the unfolding of two intertwined temporalities: economic success as a self-made woman is accompanied by growing alienation in the realm of human intimacy. For Petrus Liu, what makes Song of Dreams a work of Chinese queer Marxism is not the fact that it depicts the lives of queer identified characters. It is rather the point that the economic transformations that Zhen goes through produce multiple lacks and fissures in her life and alienate her from herself. Integrating sexual desire with the ebbs and flows of capital that structure the dispositions and worldviews of the characters, Xiao Sa sheds light on the Marxist lesson that the self is made and remade under changing material conditions. Depicting Yu Zhen’s growing wealth that is mirrored by privation of human connectedness, Song of Dreams highlights the failures of capitalism and heterosexual marriage. The novel ends with Yu Zhen gazing at her pregnant daughter, a mirror of her inability to break away from a tragically repetitive past and shame that she thought her glamorous life could shield her from. In this sense, the novel emphasises the interplay between agency and structure to provide a literary instantiation of Marx’s axiom that people make their own lives, but not under the circumstances of their choosing.

Besides analysing (social) text, Petrus Liu draws on his ethnographic experience with queer activists in Taiwan to demonstrate the difficulty of abstracting the question of queer human rights from broader political stakes and national interests. Through their interventions, queer activists illuminate the fissures in the Taiwanese government project of queer inclusivity and rights. While willing to recognise and protect those who meet a normative definition of human promoted by the state, it marginalises those who are seen as “deviant bodies”: prostitutes, people living with AIDS, transgender individuals and other who fall outside of the “gay but healthy” homonormative image. Despite the apparent advances in queer human rights, sexual minorities remain subject to a form of queer illiberalism. It is important, however, for the Taiwanese government to project an image to the global community of itself as a democratic and liberal counterpoint to the PRC. Taiwan’s future as a sovereign nation-state depends on US military protection and support, and embracing a rhetoric of diversity and acceptance towards queerness becomes a fundamental strategy to win over the sympathy of a Western audience.

In this sense, Chinese queer Marxism levels a powerful critique at the hegemonic discourse of “two Chinas”: Taiwan as a liberal counterpart to authoritarian China. It traces the normalisation and marginalisation of distinct sexual identities, while inserting this process in the broader geopolitical tensions between the PRC and the ROC. Herein lies the greatest theoretical intervention of Queer Marxism in Two Chinas, that makes it a work of interest not only for queer theory scholars, but with important lessons for China studies at large: It demonstrates that liberal democracy and social authoritarianism in the Chinas are better understood as discursive constructions than modes of production that have a meaningful correlation to social being. In effect, it traces the construction of a Chinese queer thought to deeper power-laden dynamics that see the socio-political tensions between China and Taiwan in an ecological, rather than merely comparative, register. It does not compare the civilisational process of two distinct Chinas, but rather sheds light on the dynamics that create that very distinction. Within the geopolitical contingencies of the two Chinas, Chinese queer Marxism emerges not as a previous stage in a linear history of queer liberation, one where the “liberal West” represents the highest level of development. Rather, it emerges as a way to (re)think the materiality of queer lives, to seek queer agency in the critique of transnational structures of power, and to make sense of the possibilities for sexual difference while acknowledging their inseparability from the political stakes of an unfinished Cold War in East Asia.

How to cite: Braga, Thiago. “A Work of Social Theory: Petrus Liu’s Queer Marxism in Two Chinas.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 18 Aug. 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/08/18/two-chinas.

![]()

Thiago Braga is a PhD candidate at the University of California Davis. His research lies at the intersection of anthropological theory, comparative philosophy, and art history, currently with a focus on the sociocultural registers of tea-drinking practices across China and Taiwan. His academic work has been published in Gastronomica and featured on The Diplomat, and he has also written for the Daily Maverick as a media critic. Aside from scholarly writing and cultural commentary, Thiago also writes prose and poetry in Portuguese, and is a musician. He is often found on his way to, from, or in between the United States, China, Taiwan, and his native Brazil, most likely looking for the best jazz bar in town.