📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on Nightmare Japan.

❀ Jinhee Choi and Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano (editors), Horror to the Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema, Hong Kong University Press, 2009. 284 pgs.

❀ Jay McRoy, Nightmare Japan: Contemporary Japanese Horror Cinema, Brill, 2008. 232 pgs.

Several years before the pandemic, I had the privilege of interviewing director Herman Yau at a film festival in Chicago. We spoke about the wide range of films he has worked on, including many ghost and horror movies. At the time, I found it unusual that Yau had directed just as many of these films as his “mainstream” ones, but he explained that he was drawn to these subjects because he believes in giving voice to the underserved. Yau’s films and horror movies from other Hong Kong directors are part of Jinhee Choi and Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano’s edited volume Horror to the Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema, which came out in 2009. This book pairs nicely with Nightmare Japan: Contemporary Japanese Cinema by Jay McRoy from 2008. Both books explain why Asian horror as a whole and Hong Kong, South Korean, and Japanese horror as separate entities deserve further examination.

In Horror to the Extreme, Choi and Wada-Marciano write in their introduction that the term “Asian cinema” is problematic because it lumps countries together and doesn’t account for cultural differences. Their title incorporates the “Asia Extreme” label that British film distributor Metro Tartan created in 1992 to bring Hong Kong, Japanese, and South Korean horror films to English audiences. The heyday of this label coincided with the rising popularity of DVDs and cable television.

Kevin Heffernan’s chapter, “Inner Senses and the Changing Face of Hong Kong Horror Cinema”, begins with the horrific death of Hong Kong icon Leslie Cheung on 1 April 2003. Cheung’s death didn’t just stun his fans around the world, but was also eerily similar to the demise of a character he had played in the 2002 film, Inner Senses, his last he made. Heffernan explains that director Lo Chi-Leung was inspired by M. Night Shyamalan’s 1999 film, The Sixth Sense. “Both films centre on the relationship between a repressed, emotionally damaged psychiatrist and his mediumistic, possibly schizophrenic patient.” Heffernan also says that Hong Kong horror has often mimicked US films going back to the early 1970s, but Inner Senses was also inspired by Japanese horror movies, or J-horror, like the 1999 film Ringu. Inner Senses and Ringu saw great success not only at home and around Asia, but also in Europe thanks to DVD distribution.

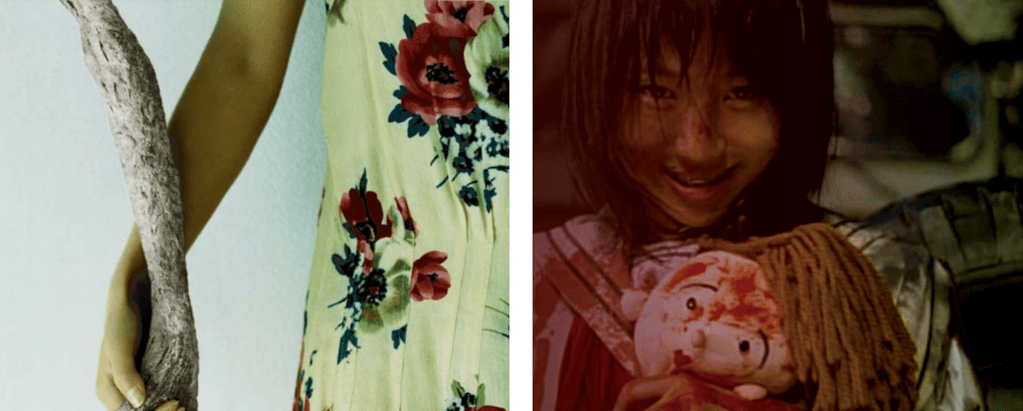

Editor Jinhee Choi’s chapter, “A Cinema of Girlhood: Sonyeo Sensibility and the Decorative Impulse in the Korean Horror Cinema”, also focuses on the late 1990s to early 2000s, just a decade after the South Korean student-led demonstrations calling for reform. The term sonyeo translates to “girls” in Korean and in the late 1990s horror stories focusing on teenage girls became popular. As Choi writes, sonyeo “has become a staple for the Korean horror genre, counterbalancing trends toward more male-oriented genres”.

Whispering Corridors is a series of films set at an all-girls high school. Choi writes that students feel pressured into staying at school late to study, so it’s only natural that they will start to tell ghost stories when they become too tired to focus on their studying. And as many high schools in South Korea are single-sex, the problems that girls encounter at school usually have less to do with heterosexual romantic relationships and more to do with issues arising between their peers or with their teachers. Friendships and same-sex relationships are usually central to sonyeo stories. According to Choi, unlike in some horror films, homosexuality is not seen as monstrous in sonyeo stories, but rather as a rejection of conformity.

Choi also writes in this chapter about the film, A Tale of Two Sisters, an eerie story of a father, step-mother, and two sisters. The cinematography gives the film a creepy feel as the sisters and step-mother appear in a frame one moment and are gone the next as they move through their house. Teenage girl horror, according to Choi, “provides an outlet for dramatising some of the conflicts with which Korean female adolescents are familiar and grants a place for representing and expressing adolescent female sensibility, which hitherto has been neglected by many mainstream genres”.

In Horror to the Extreme, only three of the eleven chapters are dedicated to J-horror, so for a closer look into Japanese horror and ghost films, Jay McRoy’s Nightmare Japan: Contemporary Japanese Horror Cinema provides a thorough analysis of this genre. McRoy’s book is more graphic—both in language and in the images depicted in the book—than in Horror to the Extreme, with more than a few images of hangings and mutilated body parts from various horror film stills.

When McRoy wrote his book in the late 2000s, Japanese film had been around for a century but he focuses on the last fifty years of Japanese horror films, so going back to the 1960s. He writes that World War II, particularly the devastation of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, greatly informed Japanese horror stories. In more recent decades, the financial recession of the 1990s and 2000s has affected the national psyche in Japan and horror movies reflect these unstable times.

Traditionally, Japanese horror movies either involved a giant monster like Godzilla that threatened to take down an entire city or involved avenging female ghosts, or kaidan. Ringu is briefly mentioned in Horror to the Extreme, but in Nightmare Japan McRoy analyses this 1998 film along with the 2002 movie, Dark Water, also directed by Hideo Nakata. In Ringu, after viewers watch a haunted video tape, they die seven days later when a ghostly woman with long dark hair dressed in all white scares them to death. When the protagonist Reiko and her ex-husband learn that their son has viewed the tape, they must find a way to reverse the curse—even if it means the death of another loved one.

Dark Matters involves a single mother and her young daughter. It’s difficult for Yoshimi to make ends meet and becomes overwhelmed one day when she’s late to pick up her daughter Ikuko from school. But Ikuko is gone, taken by her father. The spirit of a dead girl named Mitsuko takes Ikuko’s place in Yoshimi’s heart. In both of these films, the women are single, divorced mothers at a time when divorce and single motherhood was on the rise in Japan.

Other J-horror films take on masculinity and the All Night Long series by Matsumura Katsuya is representative of that. The first of the three in the series came out in 1992 and involves three alienated teenage boys who witness the murder of a teenage girl as they wait at a train crossing. They all get into trouble, often violent fights, and only one of the three emerges alive at the end. The other two films in the series are just as bleak and involve new characters with equally graphic finales.

Both of these books are fascinating in that they describe super-violent films in countries and cities that are known for their safety. The difference between American horror and Korean, Japanese, and Hong Kong horror is that the former usually involves the fight between good and evil without any overarching social message. But Asian horror gives voice to the underserved, as Herman Yau discussed, and involves the changing socioeconomic status of women in Japan, the teenage problems of girls in Korea, and the era of uncertainty in Hong Kong.

Although these two books came out about fifteen years ago, they continue to reflect the heyday of horror film in all three of these places. Now the issues in the Korean chapters have either changed or become exacerbated. Teenage girls, I can imagine, have such unrealistic beauty standards that must cause great deals of stress. And in Japan, divorce doesn’t always lead to single motherhood these days as the birth rate has plummeted even more since this book came out. But women face other issues like a colossal income disparity compared to men, while the horror films from Hong Kong highlighted in the book pertain to an uncertain era just after the Handover. The climate has changed there now, too.

How to cite: Blumberg-Kason, Susan. “The Golden Age of Asian Horror Film: An Examination of Horror to the Extreme and Nightmare Japan.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 10 Aug. 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/08/10/asian-horror-film.

Susan Blumberg-Kason is the author of Good Chinese Wife: A Love Affair With China Gone Wrong. Her writing has also appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books‘ China Blog, Asian Jewish Life, and several Hong Kong anthologies. She received an MPhil in Government and Public Administration from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Blumberg-Kason now lives in Chicago and spends her free time volunteering with senior citizens in Chinatown. (Photo credit: Annette Patko) [Susan Blumberg-Kason and ChaJournal.]