📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

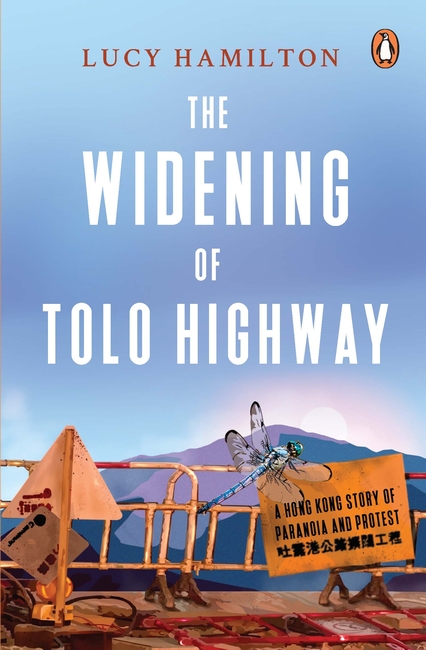

Lucy Hamilton, The Widening of Tolo Highway: A Hong Kong Story of Paranoia and Protest, Penguin Random House SEA, 2022. 236 pgs.

When, one-third into a novel, you still have no clear idea of what the plot is, you know this book is something else, in a good way. Lucy Hamilton’s debut novel, set in Hong Kong, The Widening of Tolo Highway, is one of those tales that requires the reader to engage thoughtfully as Hamilton too, through the perspectives of the book’s protagonist Anna, studies Hong Kong attentively. As Anna revisits Hong Kong three years after the 2014 social movement, coinciding with the passing of a typhoon, she finds her memories gradually coming back as she navigates places and people of Hong Kong she was once familiar with but now is no longer, including the novel’s main absentee male foil, a young teenager called Kallum Cheung.

Hong Kong is often portrayed in clichés as a glamorous, vibrant, multicultural, energetic metropole. None of this applies in this novel as Hamilton paints a Hong Kong so dark, gloomy, unsettling, anxiety-inducing, unfriendly, but still strangely captivating. Her Hong Kong has something “noir” about it; if remembrance is the novel’s main plot, hauntedness is its counterpoint. There is no graphic depiction of a physically battered Hong Kong, only various moments suggesting the looming of violence and gloom, ostensibly due to a typhoon. But the typhoon is really just a metaphor up for interpretation: one can read Anna’s psychological restlessness as a symptom of the lack of vision for Hong Kong’s future after the 2014 social movement. As the novel describes it: “[Anna]’d believed the police would help them. [… But] Kallum had told her not to trust them. They’d left the city to consume itself, one side clawing at the other’s already shrinking margin. In a city ruled by watches, they’d let the minutes elude them, let the city feel the weight of life beyond the deadline.”

Hong Kong is haunting because it is sometimes physically unsafe for a single woman. Whether it is the terrifying experience of running away from gangsters in a New Territories village, or of being locked in a taxi and held hostage for her fare, Hong Kong is not the sort of “world city” that official discourse would like us to believe. It is also haunting because it is a city of distrust: a major tension in the book is Anna’s lack of closure over the fact that the local Hong Kong family hiring her for private English lessons was trying to record her lessons unbeknownst to her, an episode that illustrates more widely how Hong Kong’s local Chinese, in their broken English, simply lack faith in globetrotting, cosmopolitan foreigners.

But Anna is no ordinary expat. She may not have lived in Hong Kong for long, but she has an amazing grasp of the flavours of life of the Hong Kong’s ethnic Chinese populace. The novel opens with a rather bleak and dark description of villages in the New Territories, and its primary setting in the town of Tai Wo, instead of the clichéd Hong Kong Island, is refreshing and rare in Hong Kong’s Anglophone writing, setting Anna apart from other Island-dwelling expats. She thus makes a sharp contrast between the different geographical constituents of Hong Kong:

If Kowloon was insanity, the New Territories was mild inertia, an oldness she could reply upon and a stasis she could trust. The Island and Kowloon had the chains supposed to comfort her: the consistency of Starbucks, the accessibility of Apple. But it was Tai Po and Fanling that had grounded her mornings: the faded lanterns at the roundabout, the broken turnstile’s peeling sticker.

Penetrating the superficial glamour of Starbucks and Apple, therefore, Anna knows deeply what it means to really get to know local contexts in depth, in the following passage that lucidly explains the difference between a mere sojourner and a local:

Before she’d met Kallum, Anna drifted like paper, looping, directionless, caught in the present. Hong Kong was a single point on a timeline that would pause when she left it, and she never thought about the past […] But Kallum’s Hong Kong was bigger. It went backwards and forwards and was always changing around him.

Even though her stay in Hong Kong is shorter than many who claim to have resided here for long, Anna’s understanding of Hong Kong is more perceptive and piercing.

Having said so, Anna is clearly aware of her distance from Hong Kong’s population, as seen in the different transcription of the Cantonese phrase for “thank you”: ‘Mm-goi’ for Anna versus Mhgòi for a taxi driver. When her mother flies in from the UK for a visit, Anna gets to cross-examine each’s biases and prejudices as a way of mediating their different critical distances from Hong Kong. Also, Hamilton cleverly introduces another layer to the expat myth with the character Lottie, who looks like just another foreign tourist but, as an expat child growing up in Hong Kong, speaks better Cantonese and is equipped with the street-smart wisdom required to survive in the city.

The sense of alienation is heightened by Hamilton’s writing technique. Both the novel’s structure (36 chapters across 230 pages) and texture (a mix of italicised passages of flashbacks with episodes in the present) highlight the scattered and obscured nature of memory. Although the chapters are short, they are not necessarily easy to read, because Hamilton’s narrator is an intradiegetic third-person narrator whose voice is reflected in dense and purposeful diction, carefully chosen to communicate not only the textures of Hong Kong cityscape but also Anna’s paranoia during her revisit. Sometimes it feels like reading a prose poem:

They huddle together beneath a canopy of umbrellas and ten-dollar rain macs. She [Anna] and Lottie hug the group’s perimeter, craving the shelter and morale of the centre. Drips from spokes make their backpacks stiff and heavy, soaking through the fabric, spoiling their supplies. (italics in the original)

It is as if Anna has her senses magnified while she is in Hong Kong. An evening stroll from Tsim Sha Tsui to Mongkok puts her not on the thoroughfare of Nathan Road, but through the narrower, adjacent Shanghai Street. Spanning two pages is her scrupulous attention to an insect killing itself on a lamppost in Kowloon Park. “Writhing” and “seizure” become “spasms” and “convulsion,” but as the insect dies, Anna imagines it as a spider “cling[ing]” and “irritat[ing]” her skin, “itch” turning into “prickle,” gyration into entanglement. Each episode like this (and there are many more in the book) studies Hong Kong as an unsettling place and explores/expands Hong Kong’s other potential representations.

Apart from being one of the most observant novels written about Hong Kong, The Widening of Tolo Highway reminds me of the term “Hong Kong as Method”, a critical expression proposed by cultural critic Professor Chu Yiu-wai. “Hong Kong as Method” posits using Hong Kong experiences as a lens to discuss any issue, in a bid to bring Hong Kong in closer dialogue with the world. In this sense, although the novel is set and grounded in Hong Kong, it presents Hong Kong as filtered through the perspectives of a British narrator, who then views Hong Kong not in the usual stereotypes of glamorous urbanism, but as poignant, suffocating and chaotic, especially in a tumultuous time. The recommendation on the back cover of the book praises the novel for being a “sharp and intense study of hauntedness”, and I could not agree more: this novel uses Hong Kong as a method for reflecting on how a city can become tormenting but curiously enigmatic at the same time.

How to cite: Tsang, Michael. “Hong Kong as Method: Lucy Hamilton’s The Widening of Tolo Highway.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 6 Aug. 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/08/06/tolo-highway.

Michael Tsang is an academic, a writer, and for the first time ever, he can call himself an “artist”. His creative works can be found in Cha, Wasafiri, Where Else: An International Hong Kong Poetry Anthology among other places. He teaches literature and popular culture of East Asia at Birkbeck, University of London. [Michael Tsang and chajournal.blog.] [Cha Staff]