📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

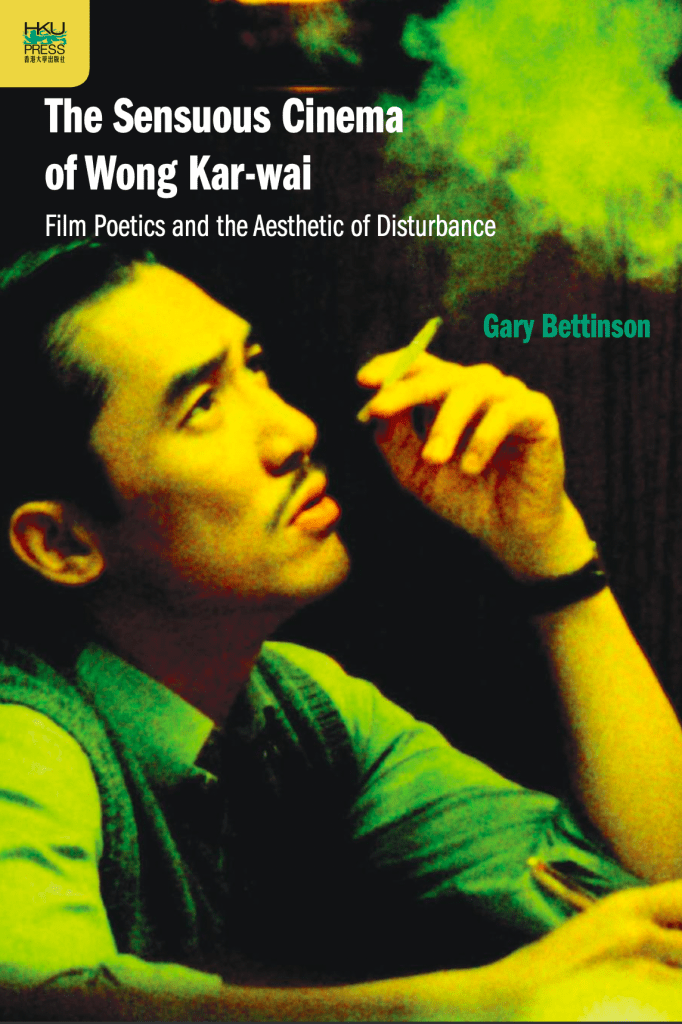

Gary Bettinson, The Sensuous Cinema of Wong Kar-wai: Film Poetics and the Aesthetic of Disturbance, 2014. 176 pgs.

In the summer of 1994, I left a cinema in Tsim Sha Tsui. It was pretty late, but instead of heading home across the harbour, I walked to a tiny shop nearby that sold DVDs and cassette tapes. I’d just seen Chungking Express (1994) and couldn’t get the music out of my mind. Hong Kong is a place of convenience and I figured if there were a soundtrack of Chungking Express, I could probably find it at this DVD shop.

It was past 10 o’clock and I wasn’t surprised to see the shop still open. I asked the manager about the soundtrack. He told me one did not exist yet as far as he knew. But he was familiar with the music in the film and pointed me to two albums, one that included Faye Wong’s Cantonese rendition of the Cranberries hit, “Dreams”, as well as Michael Galasso’s electric violin track. I bought a cassette of the former and a DVD of the latter, listening to them on loop for weeks. Chungking Express was unlike any movie I’d seen in Hong Kong at that point, yet I couldn’t pinpoint why. The music was definitely a reason, but there were also the themes of expiration dates and chance encounters that resonated in those years before the Handover.

Nearly twenty years after the film came out, Gary Bettinson wrote The Sensuous Cinema of Wong Kar-wai: Film Poetics and the Aesthetic of Disturbance, in which he devotes a whole chapter to the music of Chungking Express. He also shows how other critics have analysed Wong’s movies in top-down fashion and that it’s difficult to fully appreciate these films unless one looks at them as he does, from the bottom up. There’s so much to Bettinson’s book, but several points stand out.

Music is a big deal for Wong Kar-wai, not just in his films, as heard in Chungking Express, but also on the set while the actors are filming. I think of the B-roll footage of Maggie Cheung and Tong Leung Chiu-wai dancing on the set of In the Mood for Love (2000). And after reading Bettinson’s book, I learned this wasn’t a fluke. Wong believes that music sets the mood for the actors to get into character. Bettinson writes that this use of music during filming is not unique to Wong Kar-wai, but it is unusual in the Hong Kong film industry.

In the chapter on music in Chungking Express, Bettinson points out that four different pieces are used in the first half of the film during the Takeshi Kaneshiro and Brigitte Lin scenes, including Michael Galasso’s iconic electric violin music. In the second half of the film, which features Faye Wong and Tony Leung Chiu-wai, Wong carries over one of the pieces from the first half—a jazz theme—and includes Faye Wong’s Cantonese rendition of “Dreams”, along with the Mamas and the Papas’ “California Dreaming” and Dinah Washington’s “What a Difference a Day Makes”. Bettinson explains that each piece is intentional.

Like certain musicals, the songs in Chungking Express seem to be directly wired to the characters’ subjective states. For all its apparent arbitrariness, incoherence, and superficiality, the music score of Chungking Express—like those of all Wong’s films—displays obedience to logic, unity, and aesthetic purpose.

Bettinson includes a number of different critics and academics who have written about Wong’s films, but perhaps the most notable is Ackbar Abbas, whose 1997 book Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance is one of the most perspicacious about the future of Hong Kong. Bettinson writes that Abbas appreciates Wong’s films for addressing the time just before the Handover when Hong Kong was at a unique historical crossroads. When Abbas wrote his book, Wong’s films included not just Chungking Express, but also As Tears Go By (1988), Days of Being Wild (1990), Ashes of Time (1994), and Fallen Angels (1995). Just before and after the Handover, Wong continued to direct films like In the Mood for Love and 2046 that addressed uncertain futures.

After Wong’s first film As Tears Go By came out, he stopped using a proper script and instead pieced together his stories in the editing room, choosing from the many versions of each scene. This editing style has become a trademark of Wong’s and it’s led some critics to dismiss the artistic quality of Wong’s films. Fallen Angels is one such film, according to Bettinson, that has been not received the appreciation it deserves. Unlike Chungking Express, the stories in Fallen Angels are not separated into two parts, but are rather intertwined. Critics have viewed Fallen Angels more as a giant music video (with another spectacular soundtrack) than a film with a substantive plot. But Bettinson points out the many ways in which the movie is indeed plot-driven.

A film like In the Mood for Love has received critical acclaim, mainly for the cinematography, Maggie Cheung’s cheongsams, and the social restrictions Cheung’s and Leung’s characters face when they start having feelings for one another. Bettinson writes that Wong modelled In the Mood for Love after Hitchcock. Wong viewed this film as a thriller; Cheung and Leung figured out their spouses were having an affair and they met regularly to come up with a plan of action. The film was mainly set inside an apartment, which brings to mind Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954). In that film, Jimmy Stewart’s character is confined to his apartment because he’s in a cast and wheelchair, while in In the Mood for Love, Cheung’s and Leung’s characters hide in a room so their landlord won’t learn that they are meeting together alone while they are married to other people.

Bettinson’s book came out in 2014, one year after Wong’s The Grandmaster (2013) came out. At that time, Bettinson—no more than anyone else—could not have predicted what would happen in Hong Kong in the years to come. While most Hong Kong directors had started working with mainland production crews around the time The Grandmaster was made (it, too, was a mainland production), Wong was still more inspired by French and other European filmmakers. For almost four years, the Covid-19 pandemic has put a long pause on the Hong Kong film industry. So while it might have seemed that Bettinson’s book would be outdated nine years after it came out, it most certainly is not. As of this writing, Wong Kar-wai has not directed another movie since The Grandmaster. Consquently, Bettinson’s book is just as current in 2023 as it was when it was published in 2014.

How to cite: Blumberg-Kason, Susan. “Getting to the Heart of Wong Kar-wai: Gary Bettinson’s The Sensuous Cinema of Wong Kar-wai.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 24 Jul. 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/07/23/wong-kar-wai.

Susan Blumberg-Kason is the author of Good Chinese Wife: A Love Affair With China Gone Wrong. Her writing has also appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books‘ China Blog, Asian Jewish Life, and several Hong Kong anthologies. She received an MPhil in Government and Public Administration from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Blumberg-Kason now lives in Chicago and spends her free time volunteering with senior citizens in Chinatown. (Photo credit: Annette Patko) [Susan Blumberg-Kason and ChaJournal.]