📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Don Mee Choi, DMZ Colony, Wave Books, 2020. 152 pgs.

Reading Don Mee Choi’s DMZ Colony is an experience that plunges into a theatre of words, a theatre of pain in which words are everything. Choi turns the book into a semiotic play of anguish, cruelty and alienation, where she dismantles words, remaking, collaging and reassigning them meanings among archives, diary entries and oral testimonies, in an effort to interrogate Korean history infiltrated with war, dictatorship, and military occupation.

What is a border? This seems to be the first question posed in DMZ Colony. The opening of the book presents “DMZ COLONY” in large letters in black and white, resembling the deterrent shape of multi-fold iron gates to the forbidden DMZ (The Korean Demilitarised Zone), as if demanding a permit from the reader-visitor. The 38th parallel within the DMZ, which divides North and South Korea, appears as a thin line on the map, yet it is “one of the most militarised borders in the world” (5).

Across the speaker’s memory from the location in Saint Louis, Missouri, the speaker sees flocks of snow geese forming lines and patterns in the sky. Choi traces the flight passage of the snow geese as a metaphor in her “sky translation”, where she rewrites the birds’ transit patterns into pictographs of the letters “D, M, Z” (8). The letters, spreading across the page, form an image of birds migrating, where each letter is a bird in transit, and each letter a carrier of the severed name of the border zone “D, M, Z” across the sky. If Choi magnifies the font size to mime the threatening effect of the barricades at the border zone, she also demonstrates how words might be transformed into living creatures taking flight at different locations around the world. For birds, the borders that separate humans are non-existent. Hearing the snow geese’s call across the distance, the speaker imagines the birdsong to be the call from home:

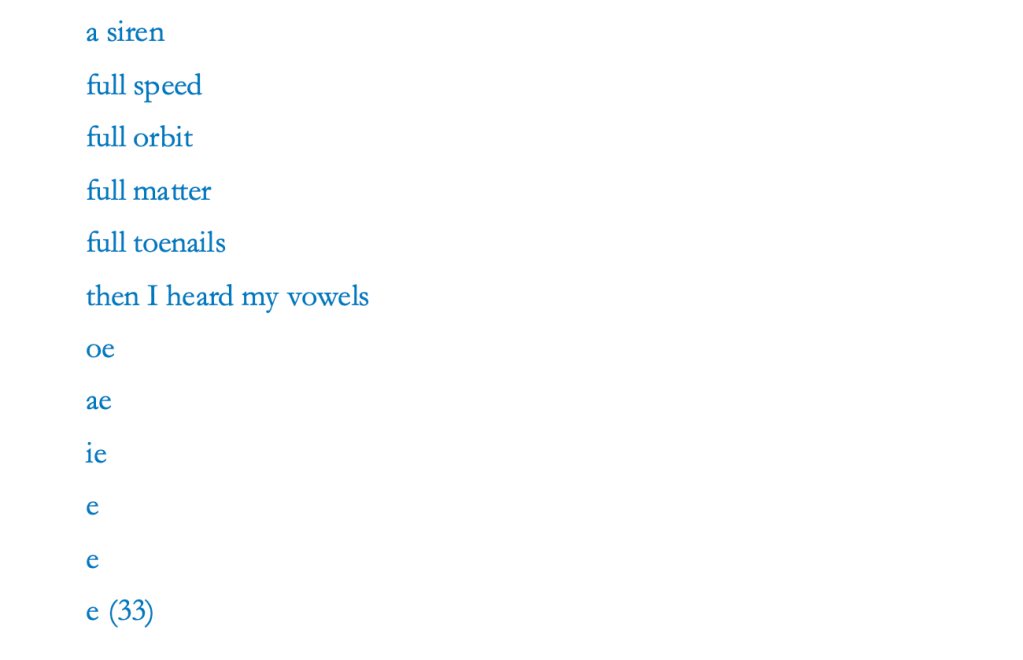

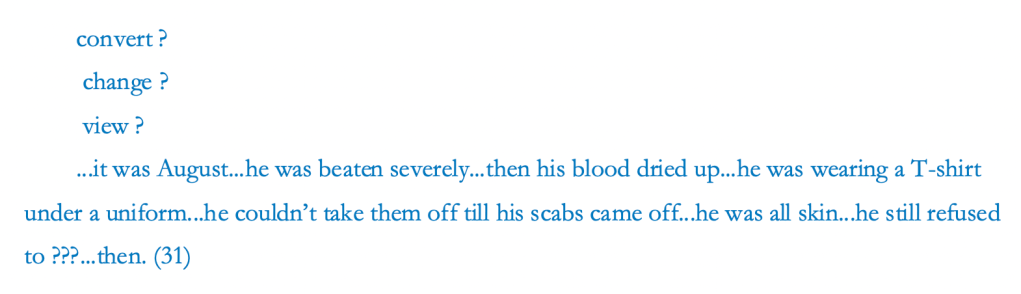

Choi refrains from descriptions or interpretation, but documents linguistic failures, transmutations, and traps from the perspective of a translator-poet. When language fails to address the scale of pain, this failure is in itself a testament to the terror and violence under the US-backed military dictatorship led by Park Chung-Hee. Where unspeakable horror robs verbal capacity, Choi presents the process of loss in the testimony of Ahn Hak-Sop, a former DPRK army officer, who was a political prisoner from 1953 to 1995 for being a North Korea sympathiser, to articulate the abyssal depth of trauma:

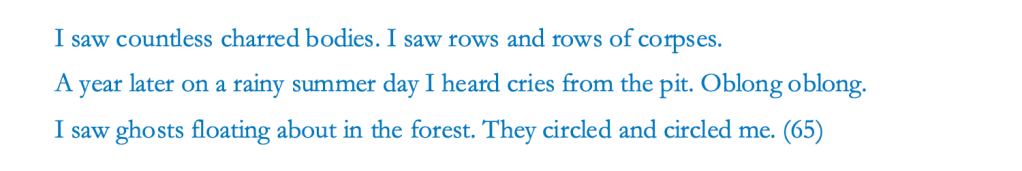

The repeated single syllable “e”, sinks like an echo through a well, losing its substance, still yearns for an answer. When Ahn Hak-Sop recalls being imprisoned, tortured and forced to change his political views, his words and sentences break into fragments of scribbles, repeated phrases, indistinguishable codes, and silence:

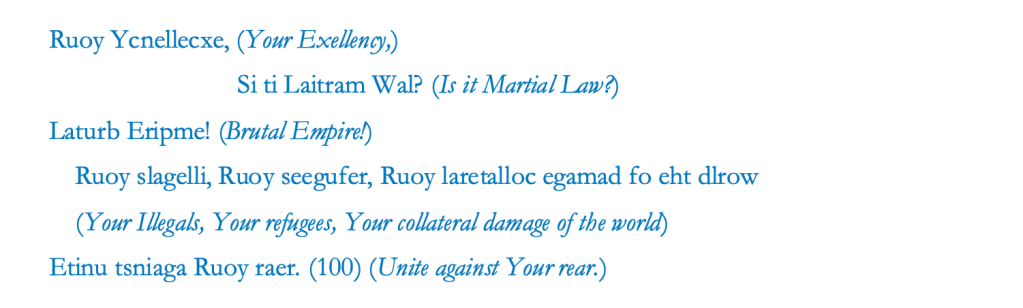

Rebuilding meanings from in the linguistic site of loss, pauses, and chaos as a translator migrating between the US and South Korea, Choi writes: “The language of capture, torture, and massacre is difficult to decipher. It’s practically a foreign language. What a nightmare! But as a foreigner myself, I am able to detect the slightest flicker of palpitations and pain. Difficult syntax! It may show up as faint dots and lines, but they’re often in blood, snow, and dandruff” (43). While broken narratives of tortured individuals conjure up an allegory of pain, Choi views the mode of translation as an “anti-neocolonial mode” (99), in which alternatives of words could be created to defy the language of torture, division and suppression. One of Choi’s variating approaches in reconstructing language from history is via the presentation of “mirror words”:

“Mirror words defy neo-colonial borders, blockades. Mirror words flutter along borders and are often in flight across oceans, even galaxies” (99), Choi writes. The idea of mirror translation in DMZ Colony extends the meaning of translation, and is in itself a poetic action, through which the poet acts as the programmer of the virtual mirror to reconfigure the texts from history. Through the display of inverted words, the poet disrupts the reading process, prompting the reader to re-imagine the stories of those who could no longer speak. As readers translate the mirror words back into their own languages, the traumatic past could be registered and re-scribed in the present.

The poet’s presence moves among history, like a phantom without a face. “‘Hey, you there!’, ‘Commies.’, ‘YOU.’” (88)—These were the language of the mass “hailing” as the Korean War broke out in June 1950 and during the Sancheong-Framyang and Geochang massacres in February 1951, under Syngman Rhee’s dictatorship. Choi recasts the scene of terror by revealing photographs and official documents, then mimics the hailing by translating the forceful speech into an urgent call to interpellate the oppressors’ language—“Now look at your words in a mirror. Translate, translate! Did you? Do it again, do it!” (99). The exclamation mark compels the reader to recall the mad, violent course of history, dragging the reader’s gaze back to the page, to look at their own reflections, to witness the violence, and translate it into resistant language.

There is a sense of absurdity deriving from the paradoxical syntax, as the speaker goes on naming who “we” are and who “we” are not—“We are all orphans, orphans who aren’t orphans. Angels who aren’t angels” (115). The confirmation and negation of identities in the sentence embeds an inequitable state of being—the colonised and the colonisers, and the yearning of being secured from the bounded relations. The “we” who are denied the identities of orphans and angels are meant to be paradoxes, in which “we” inhabit both the first and latter part of the sentence, living the experience of always being in transit, always returning to the memory, circled by victims from the brutal past:

The emergency of remembering history in Choi’s work demands the reader to be absolutely present, to be the paradoxical “we”. As the sight of birds moving across the sky could be read as signs of departure and return, each reading of DMZ Colony enacts a transition of history from within, which calls for individuals to break the silence—the last and the most essential border one can carry.

How to cite: Liu, Pareys Yiyi. “Oblong Oblong: Mirror Words in Transit in Don Mee Choi’s DMZ Colony.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 4 Jul. 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/07/04/dmz-colony/.

Pareys Liu Yiyi is a PhD student in English Literary Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She is studying contemporary diasporic poetry, interdisciplinary creative practices, and women’s writing in the Global South. She is also working on a manuscript of poetry. She worked as an editor and a teacher before coming to Hong Kong. Her writing has appeared in PEN Voices: English (2017), Jintian Journal (2020), and Enclave Magazine (2022).