📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Ozawa Minoru (author), Janine Beichman (translator), Well-Versed: Exploring Modern Japanese Haiku, with photography by Maeda Shinzō and Akira, Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture, 2021. 375 pgs.

Haiku has a bit of a double identity. There is haiku written in Japanese, and there is haiku written in other languages. On the international creative writing scene, the haiku is one of the most popular poetic forms appropriated by poets of other languages, but because of the different ways languages work, few are aware of formal complexities of the haiku and tend to only take on the more adaptable rules (such as themes of nature or the 5-7-5 syllable structure, the latter of which is sometimes considered too rigid even). Meanwhile, in Japan haiku continues to enjoy immense popularity to the extent that there are both mass-market books and TV programmes on writing and appreciating haikus. The crafting of Japanese haikus is restricted by more rules, such as the use of a single season word (called kigo) that evokes the sentiments of a particular season, or the cutting technique (kire) that produces a sharp cadence in a poem’s prosody. Deviations from these rules are often frowned upon unless a haiku poet (or haijin in Japanese) demonstrates advanced crafting skills in justifying such deviation with good intention. By and large, the Japanese haiku world is still considerably disconnected with the Anglophone haiku communities. That is, until now.

This definitive selection of modern Japanese haiku, based on editor Ozawa Minoru’s 2018 publication in Japan and now aided by the translations of Janine Beichman, an illustrious translator of Japanese literature, presents a work of art that serves not only as a very useful handbook for poets interested in learning more about the Japanese haiku, and can be a key reference text for students of Japanese poetry as well. Through this volume, poets in other languages, such as English, can learn the intricate requirements of writing a Japanese haiku.

The haikus chosen by Ozawa are written by seasoned haiku poets and are all superbly crafted. One of my favourites is this one on p. 57 which uses synaesthesia to contrast the scale of a galaxy and a plate:

Or this one (p. 261) which communicates profundity and depth in a parallel syntax simple but effective:

Indeed, poetry, too, is like a kiln constantly at work. Take also this one on p. 273:

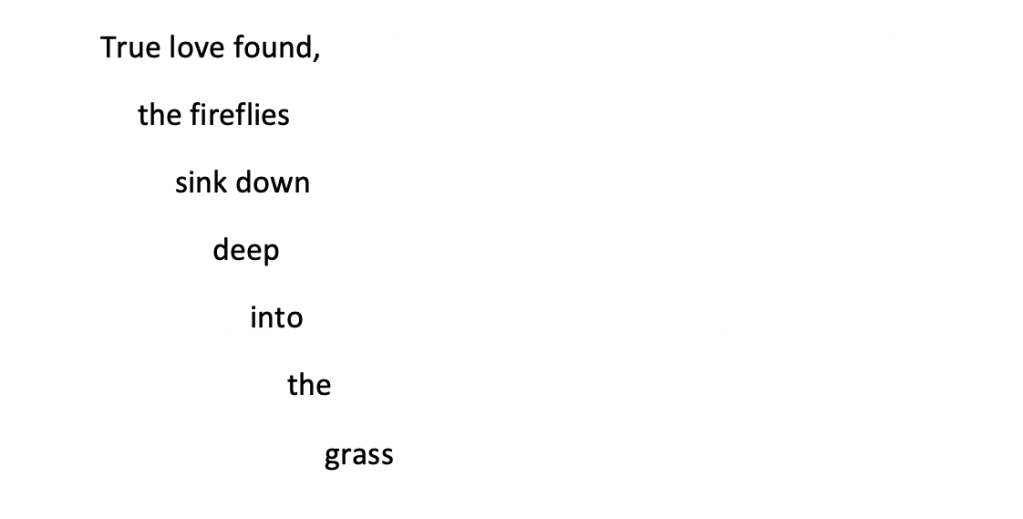

As Ozawa’s comment highlights, love is an unconventional subject matter in haiku, and a clear proclamation of sentiments via “beautiful” is also a taboo. But what may escape most English readers is that in the Japanese the ancient adjectival “utsukushiki” is used, and immediately makes this proclamation echo with the timeless ideal of love.

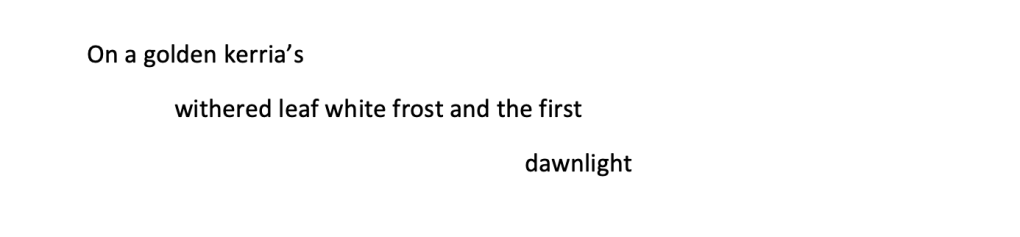

The comments I speak of here are the commentaries written by Ozawa that accompany each poem. They are rewarding to read and it is most fruitful to see them as Ozawa’s own preferred explanation and one of many possible interpretations. The commentary (called kaisetsu) is a distinct feature of Japanese publishing, usually penned by a famous writer or literary critic, but can sometimes be written prescriptively. Due to different cultural expectations and reading traditions, Anglophone readers might approach these commentaries not as an authority but as an informed viewpoint. Ozawa, indeed, is extremely knowledgeable, and the explanations are most enriching when they supplant details of the formal and acoustic features of haiku or customs of Japan, such as the consonance of the /t/ sound in a haiku on p. 33: “Tsukuzuku to / Takara wa yoki ji / takarabune.” Also helpful is Beichman’s supplementary notes introducing different groups and factions of haiku in Japan, which allows non-Japanese readers to piece together a glimpse of the vibrant haiku scene in the country. In this light I would love to see Beichman provide a little more explanation of Japanese haiku conventions, precisely to enable a global audience to understand some of the formal innovations displayed in modern haiku. An example is this poem on p.23:

This haiku contains four season words (golden kerria, withered leaf, frost, first dawnlight), which is considered a major taboo. Here, however, they present a vivid image. Not only that—and this is where I wished the explanation had gone further—but they are strung together in Japanese with the repeated use of the particle no. This particle usually expresses the possessive case, and thus the rough literal translation at the bottom of the page reads “A golden kerria’s / withered leaf’s frost’s / first dawnlight.” Beichman makes the necessary edits in the process of translation, but for foreign readers, understanding the importance of the particle no is important; it no longer expresses possessives, but helps readers zoom in from the macroscopic (a golden kerria plant, then a withered leaf) to the microscopic (to the frost, and finally the dawnlight haloing around it). It is this zooming effect that makes vivid the image, and to do this with one single particle, no, is a grammatical genius of the poem that deserves more discussion.

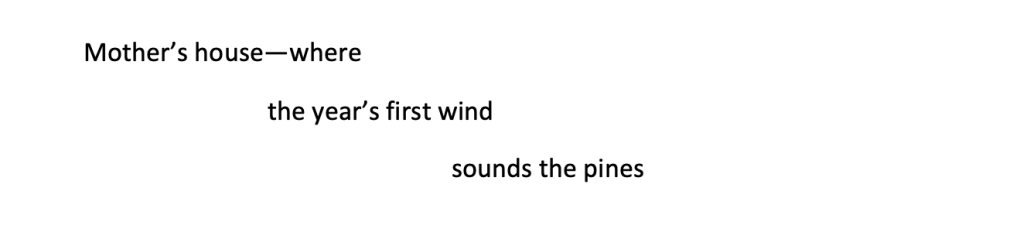

Beichman’s translation emphasises a faithful communication of the form and imagery of the source texts. The dash is often used to introduce the season word or the cutting effect. Some poems could perhaps be translated with a little more freedom. An example is this haiku on p. 28:

The break between “there” and “is” could for instance be edited instead as:

(my edits)

The word “where,” it seems to me, does an equally good job in expressing the sense of place. Of course, this is more a matter of preference and there is no right or wrong answers in translation. In this light, Beichman’s translations are most effective when they perform unconventional wordplay on the poems, such as this one on p. 155:

The use of indentation here illustrates the sinking and hence the love between the fireflies.

Ozawa’s own selection of twenty haiku poems at the end of the book are particularly music to the ears as they play with the sounds of the Japanese language: “kaerubeki yama kasumi ori kaeramu ka” (“I must go home to the mountain / misted over now— / off I go!”; p. 356). Note the consonance of the /k/ sound evoking a sense of hesitated agitation.

The book also comes with several thoughtful features: very informative biographies of the poets chosen; useful indices of season words employed; arrangement of different sections according to the seasons, bracketed by the sections “New Year” and “Seasonless” which make the book read like a Japanese saijiki (haiku dictionary); and photos of the Japanese nature by Maeda Shinzō and Maeda Akira, so beautiful that it would have been most wonderful if a few examples of haiga (or haiku-appended pictures) could be included.

There is no doubt that the book fulfils its purpose and context—to share with a global audience ways of appreciating the Japanese haiku. I hope this book can help begin a conversation between lovers of haiku worldwide, stimulating a discussion as to whether it might be productive to try adapting more of the Japanese haiku conventions illuminated in this beautifully produced volume.

How to cite: Tsang, Michael. “Beautifully Produced—Ozawa Minoru’s Well-Versed: Exploring Modern Japanese Haiku.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 24 Jun. 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/06/24/well-versed.

Michael Tsang is an academic, a writer, and for the first time ever, he can call himself an “artist”. His creative works can be found in Cha, Wasafiri, Where Else: An International Hong Kong Poetry Anthology among other places. He teaches literature and popular culture of East Asia at Birkbeck, University of London. [Michael Tsang and chajournal.blog.] [Cha Staff]