📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

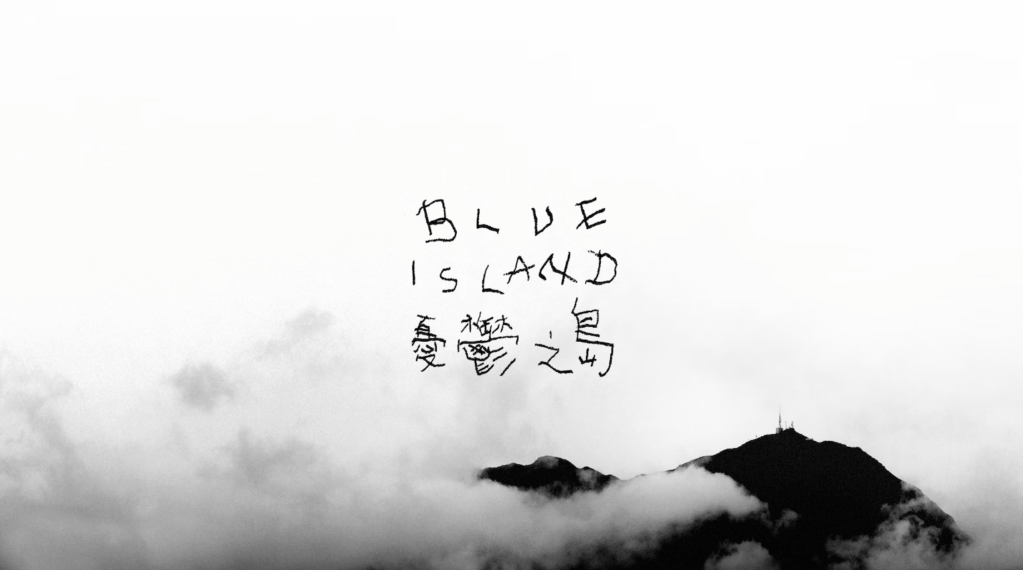

Chan Tze-Woon (director), Blue Island, 2022. 97 min.

A history student, I linger in the Hong Kong Museum of History’s condensed Hong Kong Story exhibition: one room per millennium, and “thank you for visiting” after 1997. Our story is a touching one: it speaks of hardship, of oppression under British and Japanese regimes, complete with a happily-ever-after, rewarding our perseverance. I’d be remiss if I called the exhibition an outright falsehood, because history contains manifold and nebulous interpretations of itself, its objects and its memories; but to repudiate the last twenty-six years, to deny even the reality of today, is untenable. The custodians of our history have locked up the full exhibition, like a level in a video game, until the Hong Kong people gain enough XP or they figure out how to piece together the shards of the last few years.

Chan Tze-Woon’s Blue Island is a masterpiece of narrative, one that speaks a documentary fact built on fictionalised representations of the past, starting from the 1960s. The honesty and breadth of its story, Hong Kong’s story, is everything that the Museum of History lacks.

Other reviewers have made much, and rightfully so, of the film’s remarkable treatment of a political history of Hong Kong, so I will not say more except that it fuses the mainland Chinese refugee crisis, the 1967 riots, and the Tiananmen Square massacre with Hong Kong’s contemporary strands of resistance. Young activists embody older revolutionaries, fighters, prisoners, exiles, émigrés. It’s a daring historical argument that Chan advances beneath a subdued layer of emotionality: he links events across countries and decades that official narratives would have us keep apart or even unremember, hinging them on the individuals and values that impelled them. The youth of the film—my age—could be playing out the lives of strangers as much as the lives of their own parents.

Blue Island begins with windows and ends with faces. Hong Kong is a village of wealth: apartment buildings slide into place, one above the other, like stackable stools in Kowloon’s diners. A wealth of sound: shouts echo off rectangles of light for Hong Kong. A wealth of people: in the wake of the National Security Law, the government levels charges as absurd as “conspiring to subvert state power” against deliverymen, students, and legislators alike. Chan stages a line-up of the “guilty”, an array of silent faces in a silent montage at the film’s coda. Some faces are so famous I’m surprised to find them there, then I realise that they would not be anywhere else. The credits ease into a final spillage of anonymity.

I encounter Blue Island for the first time at the East Asia Film Festival Ireland, on a hunt for my Hong Kong. The room is the union of all the Cantonese speakers on this green island, I see it in our nose tips. In the film, in the blue light of the morning harbour, a pair of young demonstrators wonder if they’d have the courage to emigrate. A student leader declares that “without Hongkongers, Hong Kong would be nothing”. The film’s faces, whether torn with rage in a black-clad Admiralty mass or singular and silent in a courtroom, are ours. We mirror the screen, like seeing your own emotions writ large in the close-ups of filmgoers in Cinema Paradiso; close-ups, in Blue Island, of petrification and anguish. At home I watch it a second time and then a third. It astounds me. It helps me.

Here, then, is Chan’s thesis: the people of Blue Island are all Hongkongers, regardless of their rights, their whereabouts, or Hong Kong’s political status. Whether they migrated to Hong Kong or were born there, whether they resisted Britain or China. Whether the riots abandoned them or consumed them. We in the cinema, riding a blue wave of tears, are Hongkongers, whether we left in courage or in cowardice. If we can’t have democracy, the film seems to say, we can at least have our history, a narrative of nostalgic defiance for Hongkongers and by Hongkongers. Perhaps to be a Hongkonger is to inherently resist something in some way.

And what about our future? Even Wong Kar-wai only ventured as deep as 2046, though we’re now closer to 2047 than we are to 1997. Twenty forty-seven isn’t a blind spot so much as it is the official flat edge of Hong Kong’s earth, though officious sources, like Blue Island or Karen Cheung’s Impossible City, are already circling the key idea: that Hong Kong might have to become a self-perpetuating concept, a regenerating wave, if the actual territory of Hong Kong alienates a large enough proportion of its population that it must cease to home their values. We are Hongkongers; therefore Hong Kong exists.

Blue Island is simultaneously a voyage home, a fight for it, a memorial for it, and a departure from it. Its elegy is true, and its eloquence far surpasses what sanitised, authorised constructions of Hong Kong’s history are able to achieve. Here is also what Hong Kong is: a plunge into Victoria Harbour; red ink for the dead; a ship rocking away from the bluest island.

How to cite: Suen, Michelle. “A Hong Kong History in Chan Tze-Woon’s Blue Island.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 23 Jun. 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/06/23/blue-island/.

Michelle Suen is from Hong Kong and is based in Dublin, Ireland. She studies English literature and history at Trinity College Dublin and is an assistant editor of fiction for Asymptote. [All contributions by Michelle Suen.]