📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart.

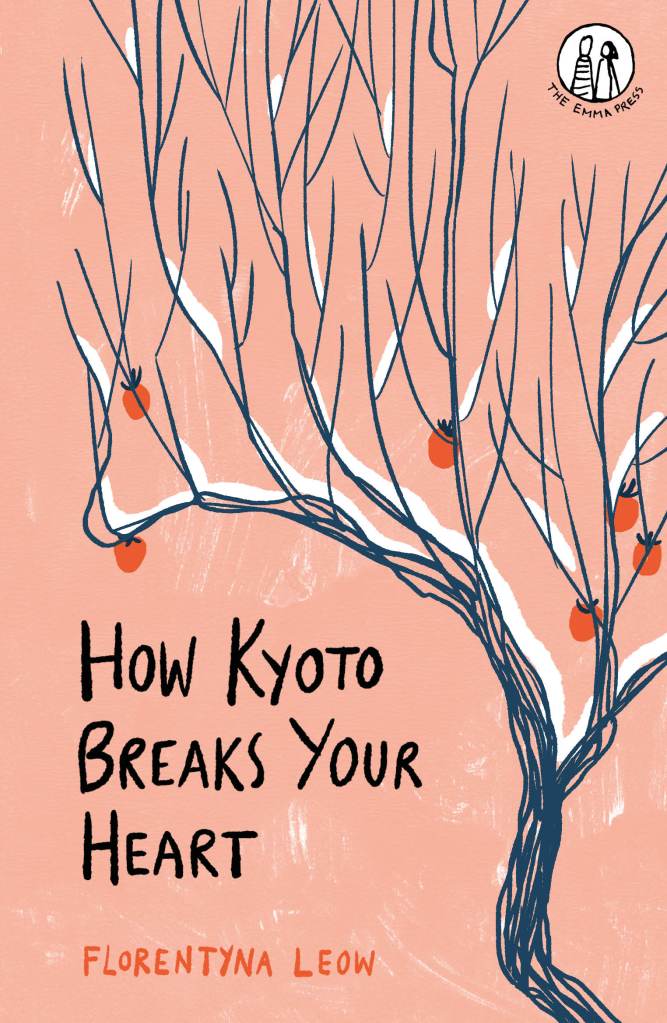

Florentyna Leow, How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart, The Emma Press, 2023. 152 pgs.

I open Florentyna Leow’s How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart to an unexpected epigraph:

To belong is to be in a relationship. Relationships take

—Zedeck Siew

time and exchange. Relationships are risks.

It’s not the statement that surprises me. After all, much has been said colloquially and academically about the bonds that transform a space into a home. What surprised me, rather, was that I recognised the name of the person to whom the quote was attributed. We’d met a few times online, talking about or playing games on Discord. On the one hand, this might reflects the small world of Southeast Asian literature in English. But, whatever might be said of that, it also brought the comfort of hearing a local word in a foreign land—the reassuring presence of the familiar in an otherwise alien space.

The travelogue genre can be alienating for me—and, I suspect, for many Southeast Asians—dominated as it is by Westerners’ perspectives. So while Japan, for instance, might be no more foreign to me than to a European, the latter can at least take solace in the familiarity of “white, usually male, Anglo-centric perspectives” that have dominated foreign perspectives on life in Japan.

In this context, Leow’s memoirs are a valuable point of contrast, or perhaps solace, in the midst of the prevalent perspectives. As a Malaysian-Chinese with multiple experiences of emigration under her belt, she is a different kind of foreigner than those who would typically introduce a stranger to Kyoto. Where some self-described gaijin might lean into Whiteness to sidestep the norms of Japan, the Leow who emerges from the page is a repeat-émigré, who attempts not merely to blend in but “to find a home in Kyoto”. And, to the extent that “no two people ever see [a place] in quite the same way”, Leow’s memoirs can also be seen as finding or making a home for Southeast Asians or other less visible foreigners within the sphere of travelogues. This endeavour depends, in large part, on the persona that emerges from the work.

The Florentyna of the book’s recollections is a young adult who left a traumatic Tokyo sales job to take up a friend’s invitation to work and live with her in Kyoto. The first episode, “Persimmons”, introduces the home at the heart of her Kyoto life: it’s a charming house built in vernacular architecture, cramped for two people but in a way that’s just manageable enough, and flanked by a large persimmon tree. It also introduces the sting of pain that runs through the book: her eventual falling out with her friend, the total loss of contact, the absence of any clear answers for why it happened. And in the wake of that separation, Kyoto ceases to become a home—even if it’s not until some time after their parting that Florentyna finally moves.

Florentyna the persona, the narrator, revisits her erstwhile home through a series of episodes focusing, in turn, on people, places or events. These include, for example: attempts at making persimmon jam; her favorite kissaten, a dim, old-school jazz cafe; attending a chaji or what foreigners often call a tea ceremony; the shopping alley she frequents and the shopkeepers she gets to know; her experiences as a part-time tour guide as Kyoto’s tourism rapidly booms—right until the pandemic of 2020.

Perhaps it’s because of this side hustle that Leow’s subjects seem to have a touristy bent, even as she disavows a travel guide approach to writing. She might avoid delving deep into Kyoto’s history, its temples, shrines, and strikingly dressed maiko, but the ways she waxes poetic about tea, for example—“to enter the tearoom is to literally step into another world”—wouldn’t be amiss in any other guide to the city or, indeed, to what most people conceive of as quintessentially Japanese culture. But then again, it would be unfair to expect her to be any more immune to the city’s charms than she already is. Her appreciation of Kyoto’s beauty is what you’d reasonably expect of someone living in a city committed to being traditionally beautiful. And indeed, many of the things she is drawn to are things that my friends and I—ourselves urbane, well-travelled Southeast Asians with a fondness for Japan—sought out the few times we visited the country: quiet independent coffee shops with a laid-back atmosphere, specialty tea shops where the drink is served alongside traditional snacks, the comfort of a jazz record played on a phonograph, the calming beauty of the Kamogawa.

Rather, one might say that the persona’s fondness for the city as a resident nonetheless finds expression through her habits as a tour guide. Indeed, the blurred boundary between her professional persona and the rest of her life is a problem that she herself acknowledges:

I found myself slipping into ‘guide mode’ with friends, deciding where to eat, pouring their drinks, launching into explanations of things around us, then resenting their lack of initiative. Traits that served me well in my job […] proved disastrous for real-life relationships, and I’d resent the other person for refusing my attempts to please them.

Nor is it the only trauma she struggles with. Her sales job in Tokyo, she notes, left her with a propensity to please people—“to bend, to shrink myself, to bow in the face of other people’s needs and desires”—that her tourism job only exacerbated, and which she struggled to unlearn in the gap between her life in Kyoto and the time of writing.

This is yet another chorus in a familiar language: that of the Millennial constantly looking to hustle, to make ends meet, to survive in the face of inflation, the precarity of the gig economy, and two dozen other concurrent crises. Florentyna’s anxieties, insecurities, and evanescent personal boundaries could easily apply to many of my own cohort.

Yet this familiarity, I realise, poses its own problems. In drawing on places, images and turns of phrase to explore “all the ways you can love a place” and “let it break your heart”, the book sidesteps, if just barely, the true ache at the heart of its episodes. To some extent, this is only proper: as the author notes, some sides of that story are not hers to disclose. And perhaps some that she could divulge would serve only as fuel for a vicarious yet egregious misery. Still, where this book chooses prudence and restraint, it perhaps loses out on catharsis.

Still, there are moments in Florentyna’s recollections I find especially resonant. Her fondness for kakigori over “the rough-hewn ais kacang at home I’ve never liked” feels like familiar territory. Nearly half of Southeast Asia seems to have some crushed ice dessert it’s proud of. While I wouldn’t say I’ve never liked halo-halo, I’d be lying if I said I didn’t prefer kakigori.

And then, of course, there’s the “constant code-switching… between different modes of English and barely-conversational Chinese… and Malay”. The power-play of language is a constant in Southeast Asia, where English dominates as the language of the wider world, while local lingua francas serve as a necessary bridge across disparate nations consolidated under colonial rule, and regional languages and dialects struggle to make themselves heard. Moving between Tokyo and Kyoto, Florentyna finds this mirrored in the tensions between conventional Japanese and the more “lively, warm” Kansai-ben, which “felt closer to how [she] wanted to speak.” She finds common ground in the words of an acquaintance from Fukui:

It turns out the other person has to be speaking the same dialect for his accent to emerge. It’s the same for me. Going back to Kyoto… brings it all back. I shed the stodgy linguistic weight of the big city. My speech loosens, lightens, brightens. For the few days I’m there, my Japanese comes alive again.

Perhaps my favourite chapter, though, is the one in which Leow speaks of rain. “The sound of rainwater is the surface it strikes,” she writes:

The rain is different now, where I live in Tokyo. There are no frogs. Rain now sounds like tin roofs and concrete walls, sharp and manmade. There was a recent, unseasonably cold October night I lay awake for three hours while it rained outside. It wasn’t the sort of heavy rain I could fall asleep to.

Again, this is rooted in quite personal reasons. I believe there are few things that manage, quite like rain, to make you aware of where you are. Rain that patters gently on a cafe window might pelt angrily on the sheet metal roof of a small bus stop; rain in a foreign country can seem cold and inhospitable—literally, if for example you encounter temperate rains after a lifetime of tropical showers. It’s something I had thought to myself quite often, comparing rains in London, New York or Japan to those of my own home country. Yet this was the first time I’d read someone write of it so deliberately and attentively.

In discussing rain, Leow reflects on the Makoto Shinkai animation “Garden of Words” (yet another indication of a shared cultural milieu). The movie centres on a student and teacher who meet on rainy days, kindred truants under the shelter of a shed in Shinjuku Gyoen. “Their relationship isn’t quite platonic, romantic, or erotic; two people, alone together, taking shelter in the rain.” The two bond over a pair of tanka (a Japanese poetic form) that comprise a prompt-and-reply.

In some ways, Leow’s travelogue-memoir evokes a similar situation. Much about her persona remains elusive. Yet there is clear common ground. There is a familiar language: almost like one verse finding its proper answer in another. And while How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart offers no closure, no emotional catharsis, it does provide comfort—shelter amid unfamiliar rains.

How to cite: Santiago, Ari. “Shelter Amid Unfamiliar Rains: Florentyna Leow’s How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 18 Jun. 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/06/18/your-heart/.

Ari Santiago graduated with an MA in Literary and Cultural Studies from the University of Hong Kong, and is currently based in Metro Manila, doing freelance and independent work in content marketing, tabletop game design, and narrative design for games. Their work has been published on Play Without Apology. [All contributions by Ari Santiago.]