Memory From 4 June 2022

My father, now aged 55, used to work as a journalist in the local branch of a renowned state media in Jinan, the capital city of Shandong province, when he was my age, before setting foot in business, before joining one of the minority political parties, and way before meeting my mother and later separating from her. I have inherited his (very much politically speaking) untameable free spirit which developed while he was working within the state propaganda system. Up until the present day, I had trouble telling whether such spirit does me more good or harm, both as a political science student researching Chinese politics and as a member of the “Chinese” diaspora regardless of what “Chineseness” means.

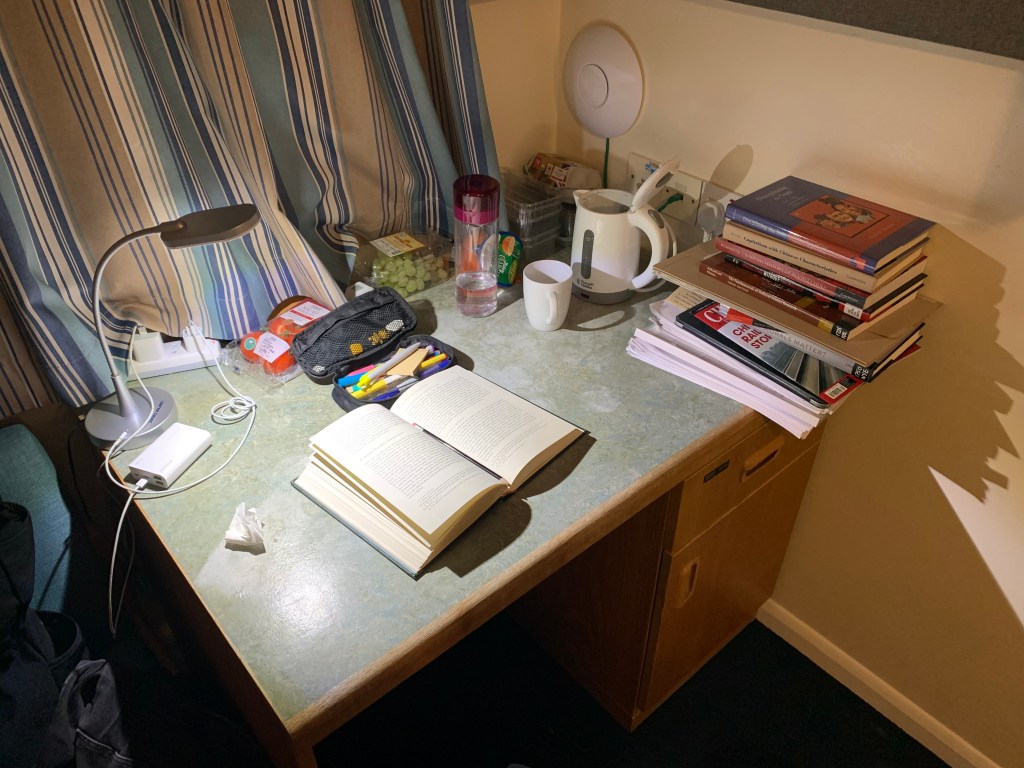

In September 2021, I travelled to the UK to study philosophy, politics and economics at the University of Oxford as a visiting student. It was the most fulfilling year of my life as I attended a wide range of lectures, binge-read books banned in the mainland on and beyond the required reading lists, and met like-minded faculty and friends from diverse backgrounds. On 4 June 2022, before leaving the UK, I wanted to revisit what happened 33 years ago, as if this was the one-and-only chance left in my life. Bewildered amongst the sea of books stored in the Oxford Dickson Poon China Centre, I picked up Dingxin Zhao’s monograph The Power of Tiananmen: State-Society Relations and the 1989 Beijing Student Movement published over 20 years ago. The book offers a fresh perspective of studying contentious politics from a geographical perspective, as Zhao detailed in the book how the location and interconnectivity of streets, college campuses and police stations in central Beijing influence the mobilisation and concomitant state repression of protests led by students. Apart from the book’s theoretical insights, I related to Zhao’s deep concern for China’s delayed political modernisation as he wrote at the dawn of the twenty-first century. I shared his quotes from the book on WeChat, but they were soon censored and removed by the platform. I already self-censored my post, as all I shared was an image containing texts in English. But all to no avail.

Academic jargon in political science—be it democratisation, rising power, or party-state—are overly all-encompassing to capture with granularity how individuals act and react to politics in quotidian lives. With many of the books I carried home from the UK being inspected and later confiscated at customs between Hong Kong and Shenzhen, I can no longer indulge/numb myself in reading printed books related to Chinese politics like I did a year ago. What used to be taken for granted now becomes a fading privilege. While books can be confiscated, ideas cannot. The sole act of sitting at my desk and regathering my thoughts also constitutes a way of reminiscing, and an act of resistance. The personal is political.

How to cite: Zhang, Jan. “Just Another Day: Jan Zhang.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 4 Jun. 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/06/04/jan-zhang.

Having studied at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the University of Oxford and Yale University, Jan Zhang has a particular interest in enquiring topics related to social inequality and civic engagement. At present, she is working on a project investigating the class identity of female migrant workers working in Shenzhen, southern China.