📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

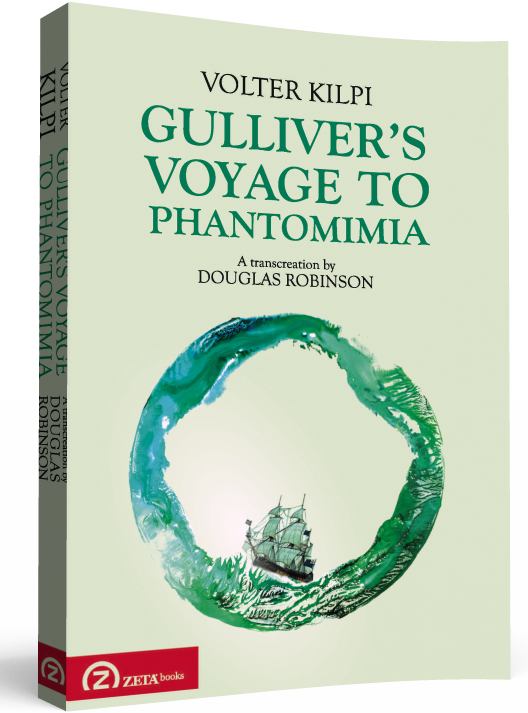

Douglas Robinson, Gulliver’s Voyage to Phantomimia: A Transcreation, Zeta Books, 2020. 356 pgs.

I imagine, that in the Great Deluge, 2 sworn Enemies, having clumb up onto the same Branch, would cling to each other, as the last Neighbours they’d embrace before dying; & that a Man with a Death Sentence, before his Execution, would, as his last Deed, brush his Sleeve ’gainst the Executioner’s Arm; for the Executioner is, after all, a Neighbour, who stands in his Presence.

—Robinson/Kilpi/Gulliver/Swift, p. 242.

1

On page 229 (of a total of 364), which is near the start of Chapter VI (titled “Gulliver marvels, & quails, at the Sensations of flying above the Earth’s Surface. His 3 Companions in the Aeroplane seem unfaz’d by the Experience”) of Book Two (titled “In Phantomimia”), I closed Volter Kilpi’s Gulliver’s Voyage to Phantomimia, looked at the ceiling, recalled reading William Faulkner, did some mental tabulations, and then started reading the text again from the beginning.

2

Let me too recommence this review of Douglas Robinson’s “transcreation” of Volter Kilpi’s “translation” into Finnish of Lemuel Gulliver’s “lost” “G5” manuscript.

3

At the point where Gulliver and the other three remaining Swallow Bird crew members find themselves being airlifted from the North Pole to Phantomimia by the members of the British Geodetickall Club Expedition (a coterie also termed the “London Geodetic Club”, the “British Geodetic Club” and the “Phantomimia Geodetic Society”, so Robinson reminds readers in fn. 4 on p. 197 and in fn. 21 on p. 250), I closed Robinson’s “transcreation” of Kilpi’s uncompleted “translation” to restart the “critical edition” (as it’s characterised, [rhetorically distancing] scare quotes included, on the book’s back cover). What I mean is, as can happen when I read Faulkner novels (Requiem for a Nun included), I felt I would have a greater purchase on––a more confident grasp of––Robinson’s Kilpi/Gulliver/Swift text were I to redouble my efforts, i.e., were I to start over.

4

The problem with beginning, with starting over, and doing so with this text especially, however, this text that allegedly made it into the hands of Deleuze and Guattari in the late 1970s (so we learn in fn. 19 on p. 246!), concerns pinpointing where exactly the beginning is. Certainly, the first page of the book, of Volter Kilpi’s unfinished manuscript of Lemuel Gulliver’s fifth voyage (i.e., the “G5”), titled Gulliver’s Voyage to Phantomimia, can be understood as a beginning. But the text of said so-far unreported “G5,” purportedly ensuing Gulliver’s recorded voyages to Lilliput (G1), Brobdingnag (G2), Laputa (G3), and the Land of the Houyhnhnms (G4), does not start until page 71 of Volter Kilpi’s Douglas Robinson transcreated Gulliver’s Voyage to Phantomimia.

5

As a “critical edition”, the book Gulliver’s Voyage to Phantomimia does not commence with Gulliver’s Voyage to Phantomimia. Rather, Robinson’s “transcreation” of Kilpi’s G5 opens with a series of paratexts, of contextualizing texts concerning Kilpi’s main one. These paratexts include (i) an editor’s foreword, (ii) an anonymous “Vorticist manifesto”, (iii) Kilpi’s own translated “Translator’s Introduction”, (iv) a reader’s report, and (v) the publisher’s postscript. As Saussurian supplément, these paratexts do not compete with one another. Nor do they collectively work to destabilise the meaning of the G5. Nor are these performatively scholarly paratexts pompous.

6

If anything, the edifice Douglas Robinson builds around the late Kilpi’s unfinished manuscript—“a hefty bindle” with a maritime “tell-tale tang” that Kilpi himself claims to have discovered by chance on his librarian desk—is Sternean. Like Laurence Sterne, and like Swift and Rabelais before Sterne, and like Steven Hall, and like Junot Diaz, Danielewski, Foster Wallace, and Nabokov, Robinson delights in cognition, the comedic, and the arcane—all delivered jocoseriously (à la Buck Mulligan).

7

Readers of James Joyce may recall the high modernist author lamenting the fact that reader-reviewers of Ulysses overlooked its (“Stately [and] plump”) humour, the very humour that might work to reduce the distance between the magisterial auteur and the humdrum hoi polloi. Pre-emptively all but guaranteeing that G5 readers do not (naturally) dismiss Professor Douglas Robinson as a pontificator from on high, Robinson (himself) tells himself to tone it down at the onset of the “Editor’s Foreword”: “Back off a little, Doug. Take it down a few notches.”

8

In the role of “Doug”, a role that persists through the book’s 101 footnotes (24 of which are in the five “Introductory [Para]Texts”), Prof Robinson satirically lambasts the figure of Prof Julius Nyrkki, whose professorial crucifixion of Robinson’s “scurrilous” translation of Kilpi’s G5 appears in the opening paratexts as “4. Julius Nyrkki, ‘Reader’s Report for Douglas Robinson’s travesty of Volter Kilpi’s unfinished Finnish novel Gulliverin matka Fantomimian mantereelle’”. Nyrkki, so we learn at the end of the 20-page report, is a barely disguised alter ego of Robinson. Noting Nyrkki’s notes on his own notes, in fn. 11 (the last words of this 4th introductory paratext) Robinson playfully avers,

Oh no? What is this paragraph, if not a response to my footnotes? [Ed.] Truth be told, I wrote this ‘reader’s report’ as a rather hysterical attack on my work precisely in order to draw your attention to aspects of the text that I’m especially proud of. [Au./Tr.].

Here, Robinson at once testifies to his critical chops (like the proverbial “reviewer 2”, he can discipline any critical positioning) and attests to his post-structural poise—not too unlike in Danielewski’s House of Leaves, Robinson marshals the roles of author, editor, and translator.

9

As I have written elsewhere, Mark Z. Danielewski’s 2000 text House of Leaves is “an edited novel about a partial manuscript about an apocryphal documentary about a haunted house owned by a [filmmaker] based on [suicide] Kevin Carter”. Robinson implements a similar recursive mise en abyme to/in his reimagining of Kilpi’s unfinished Gulliverin matka Fantomimian mantereelle manuscript. As we learn in the third introductory paratext, formally titled “Volter Kilpi, ‘Translator’s Introduction’ (1938, translated by Douglas Robinson)” in the Table of Contents, but appearing on page 43 under the slightly altered heading “Volter Kilpi, ‘Translator’s Preface’ (1938, translated by Douglas Robinson)”, Kilpi himself contends to have suffered near “shock” when the “hefty bindle” secreted onto his desk is revealed to be “sketched” by the “familiar name Gulliver”. Robinson reports that Kilpi reports that “Lilliput, Brobdingnag, [and] Laputa promptly sailed across [his] imagination” as he, Kilpi, came to appreciate “the full significance” of Gulliver, “the scribbler’s work,” work “obviously gnawed at by a nervous agitation, as if every stroke [was] sliced with the sharply honed kirpi of human rage”.

10

The word “rage”, whether Kilpi’s own or Robinson’s interpolation, is well placed, particularly when it comes to Jonathan Swift. Alongside Alexander Pope, Swift is celebrated for his work during the Golden Age of Satire. Besides Gulliver’s Travels (1726), Swift is well known for his originally anonymous satirical essay “A Modest Proposal” (1729), wherein the atheistic clergyman—cf. fns 1 & 2, pp. 329 & 330, respectively, for editor Robinson’s biographical glosses of Dean of St Patrick’s Jonathan Swift, DDiv.—concocts a scheme for (so his subtitle sets forth) “Preventing the Children of Poor People in Ireland from being a Burden to their Parents or Country, and for making them Beneficial to the Public”. Swift “modestly” proposes wealthy landowners and other similarly well-heeled Irish persons of “quality and fortune” start buying and eating the “excellent nutritive meat” of bothersome beggar’s children. Swift is careful to note that the skin of these baby carcasses when “artificially dressed will make admirable gloves for ladies, and summer boots for gentleman”. Swift’s proposal would also carry the following social benefit: “Men would become as fond of their wives during the time of their pregnancy as they are now of their mares in foal, their cows in calf, their sows when they are ready to farrow; nor offer to beat or kick them (as is too frequent a practice) for fear of a miscarriage.”

11

To put it plainly, were the (originally) anonymous author’s unassuming scheme put into place, one of several advantages might be that poor Irishmen would treat their fecund wives as kindly (or as non-violently) as they treat their barnyard beasts—nutritive animals, that, upon quick reflection, may in fact be just as sentient (as full of feeling; as affected by corporal agony) as human infants!

12

One of the more concise definitions of satire is “anger refined into art”. We may couple this ire, this rage, with irony, succinctly understood as “the intended meaning being the reverse of the literal meaning”, in order to grasp what Swift orchestrates in “A Modest Proposal”. When he humbly proposes that the Irish should start eating their babies, he’s really exaltedly intoning that the Irish must stop eating their babies. Swift levies this charge of cannibalism—figurative and literal—to all and sundry in Ireland, not just the moneyed engineers of colonial, linguistic, and religious imperialism. The poor too are responsible; they are not simply passive receivers. All (human) animals—disenfranchised and not, more equal and not, anguished and enchanted—are responsive and responsible.

13

Said personal agency sits at the heart of Douglas Robinson’s “transcreation” of Volter Kilpi’s uncompleted Gulliverin matka Fantomimian mantereelle, which Kilpi claimed to have first found and then translated from Swiftian early modern English to Finnish. Robinson coins the term “transcreation” to capture his work as translator, annotator, editor, and author (or completer) of Kilpi’s “found” text. Playing along with the Saussurean deferral that Kilpi championed, (this predates Derrida; Kilpi died three decades before the publication of “Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences” [1967]) Robinson retranslates Kilpi’s translation to Swiftian English and finishes the incomplete SF narrative, effectively time-travelling Gulliver and his three surviving shipmates from 1938 London (Phantomimia) to 1738 Blyth, Northumberland—a journey that involves a pit stop at the Siege of Jericho. But this consecrated detour is not in situ, circa 1400 BCE. Again accentuating deferral à la House of Leaves and The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, Robinson transports Gulliver et al not to Canaan itself (where they’d converse in Hebrew), but rather to Canaan as represented in the King James Bible (1611). Fittingly, Book Three of G5, titled “In the Conquest of Canaan”, is rendered in Jacobean English, i.e., “The English Idiom of the King James Bible”, as Gulliver, who narrates this fifth adventure in first-person throughout, observes (pp. 330-31).

14

In order to conclude this too brief appraisal of a text that is itself “a temple of texts” (to borrow a locution from William H. Gass), let me fold back to my beginning. I restarted reading (from the very beginning, paratexts and all) at page 229 because I didn’t want to miss anything, which is another way of saying “I feared I might have missed something”. This tends to happen when I read William Faulkner, whose poetic prose and plotlines I love, and who demands my undivided concentration; otherwise, I might find myself three hours and 60 pages ahead without recalling what exactly I’ve just been suspending my disbelief for. The same sometimes happens to me when I read verse. Occasionally, it’s as though, to quote Prince Hamlet, “the readiness is all”—and if I don’t mentally perform that self-willed paradigm shift before reading poetry (and Faulkner) I won’t be steeled, i.e., I won’t “be ready”—regardless of whatever imminent/immanent ending.

15

But it turns out that, when it comes to Robinson’s transcreation of Kilpi’s Gulliver’s Voyage to Phantomimia, I hadn’t “missed” anything. Almost every page (and almost every footnote) was etched with my pencil engravings. Rather than missing out on plot events and/or textual ephemera, large and/or small, I’d simply had a fear of missing out: FOMO. Said fear, may be understood as a marker of our uneasy present, where obsolescence so swiftly consumes the new-fangled, thus propelling human agents to capture/frame/encode every instant as lasting proof of having “truly lived” (this, of course, in an era also defined by the leitmotif YOLO, you only live once).

16

I restarted G5 at the point where Gulliver and the three other Swallow Bird shipmate survivors, whose journey started in 1738 Gloucestershire, are being transported from the North Pole to Phantomimia by aeroplane in 1938, this after having survived a 100-page journey (and an indefinite because unmeasurable period of time aboard the Swallow Bird) travelling through the “polar vortex”. The lines I read before sitting back and turning back find Gulliver naturally continuing to fear for his physical life. Yet, at the same time, Gulliver also comes to phenomenologically appreciate his own existential predicament. These long lines, amounting to just four sentences (in the Defoe and Swift style of the early English novel), appear as follows:

’Twas in Deed a loud, Ear-splitting Rumbling; our metallickall Casing rattl’d & shook, as if ‘twere gasping. It felt quite light, of course, disconnected, as we flew upward, rising & rising, into Oblivion; as if jeering at All, that remain’d below; & reaching up, & up, as the Air Currents sibilated Side-ways round us; the Engines, all the While, thund’ring, as if the Life-less Metall knew, in its Joynts, how cruell was its Quarrel ’gainst Nature. I cannot say, which Sensation was the stronger: The Rapture, at Man’s Conquest of the Air, with this Freedom; or the Horror, that Man had so stripp’d away Life’s Senses, with this Violence. I was, My-self, manifestly enraptur’d, to the Poynt of Ecstacy, at the unwonted Celeritie of our Flight; —the Nihilitie, as ‘twere, with which we plung’d upwards;—but e’en more closely crowded in upon me the crushing Terror, that I should presently be depriv’d of my Senses, & that Life It-Self would be then beguil’d from me, in the Precipitancy of our Passage. (pp. 228-29)

In fn. 34 of Book Two, i.e. 41 pages following Gulliver’s patently modern recognition of “Nihilitie & Terror” (which may be a nod to father-of-existentialism Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling [1834]), Robinson reminds readers of the existential angst—or the “Spirituall Ague” (p. 237): oh, selcouth modernity!—that swiftly supplants the beguil’d Gulliver’s original “quailing” fear for his life. In his pose as Editor, Robinson charmingly concedes,

It would be easy, I suppose, if one assumed that Volter Kilpi wrote this novel first in Finnish, to accuse him of overblown antimodernist narcissism: Gulliver had never, anywhere, felt as insignificant and non-existent as he did walking through a crowded restaurant? Yes, the first nine and a half chapters of Book Two are undeniably rather pathetic grumbling about modern life in the big city! But when one remembers that this was written in the 1730s or 1740s, about a possible future that could have proven wildly unrealistic, Gulliver’s exaggerated whining about alienation and dehumanization in the early-twentieth-century metropolis is actually quite an interesting moment in the history of literature. (p. 270)

17

Let me conclude—finally, though I’ve barely unfurled the Swallow Bird’s jib—by echoing Prof Douglas Robinson, albeit minus his artful gross understatement. Robinson’s transcreation of Volter Kilpi’s unfinished Gulliverin matka Fantomimian mantereelle is itself a remarkable moment in the history of literature. Making neighbours of us all, Gulliver’s Voyage to Phantomimia expertly integrates the best aspects of the best experimental & ergodic novels of our modern times. Robinson’s G5 transcreation sits very well alongside Abrams & Dorst’s S. (2012), Hall’s The Raw Shark Texts (2007), Danielewski’s House of Leaves (2000), Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (1996), Moore and Gibbons’ The Watchmen (1988), Baker’s The Mezzanine (1986), Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), Nabokov’s Pale Fire (1963), and Gaddis’ The Recognitions (1955). Texts this accomplished, this engaged, this informed, this enjoyable, this rereadable, really are rare gifts. They are conjured, or in this case are partly unearthed, in English at least, at most once or twice a decade.

How to cite: Polley, Jason S. “What is He Doing Playing Fantastickall Fictive Games with Realitie? Or, A Pandemonium of Embraces: Luxuriating in Douglas Robinson’s Transcreation of Volter Kilpi’s Unfinished Gullier’s Voyage to Phantomimia.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 3 Jun 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/06/03/voyage.

Jason S Polley is associate professor of English at Hong Kong Baptist University. His research interests include Indian English fiction, comics nonfiction, and North American fiction. He has articles on John Banville, District 9, Jane Smiley, Watchmen, Wong Kar-wai, House of Leaves, Bombay Fever, Joel Thomas Hynes, R. Crumb, critical pedagogy, and David Foster Wallace. He’s co-editor of the forthcoming collection Everyday Evil in Stephen King’s America (2024) and of the essay volumes Poetry in Pedagogy (2021) and Cultural Conflict in Hong Kong (2018). [All contributions by Jason S Polley.]