{Written by Matt Turner, this review is part of Issue 46 of Cha.} {Return to Cha Review of Books and Films.}

David Clark, China-Art-Modernity: A Critical Introduction to Chinese Visual Expression from the Beginning of the Twentieth Century to the Present Day, Hong Kong University Press, 2019. 256 pgs.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the writer and critic Lu Xun published several volumes of European woodcut prints. Woodcuts had become a medium of interest for him because of their immediacy as well as their economical qualities, and he enthusiastically promoted them as a new way ahead for Chinese art. In 1931, he organised a workshop for younger artists to learn woodcut techniques—drawing from the medium’s roots in Ming and Qing folk art, as well as in European modernism—in particular German expressionism. The workshop had grown out of a broader engagement with the new modalities of art production and exhibition in China, especially the shift from academic and sponsored work to private showings that sought to create both new public spaces of engagement but also explore art as an autonomous medium—despite the fact that, aside from growing popularity, arts infrastructure was not strong. David Clark’s historical monograph, China—Art—Modernity: A Critical Introduction to Chinese Visual Expression from the Beginning of the Twentieth Century to the Present Day, traces the beginnings, and consequences, of this.

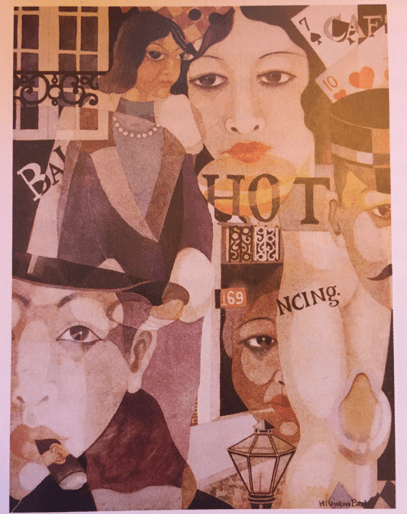

Earlier work by avant-gardists, many of whom had spent time studying abroad in Europe and Japan, sometimes even with contemporary vanguard artists, can be seen in collage and painting—such as works by Pang Xunqin, a member of the Shanghai-based Storm Society, that resonate with the work of Dada artist Hannah Höch. The field of ink painting, commonly portrayed as conservative, was particularly rich for change—and it had had new life breathed into it during the nineteenth century by artists who were also influenced by new and foreign art and new and foreign methods, introducing degrees of painterly realism and realistic subject matter that overlapped with compositional “vagueness”.

Conversely, Lu Xun’s woodcut anthologies and workshop inspired many new artists seeking to use new, expressionist-influenced woodcut prints to convey more straightforward political messages. Notable for this was Guangzhou artist Li Hua, whose work transitions from Romantic realism to political expressionism. However, following Mao’s Yan’an talks on art, and especially the subsequent 1949 revolution, “such Western modernist resources as German expressionism became less prominent among left-wing artists”. Woodcuts became overtly political and even dogmatic, but also mined the rich history of China’s folk art while “importing” new subject matter. The goal of the new art was to reach as many as possible, with clear (and officially recognised) messages.

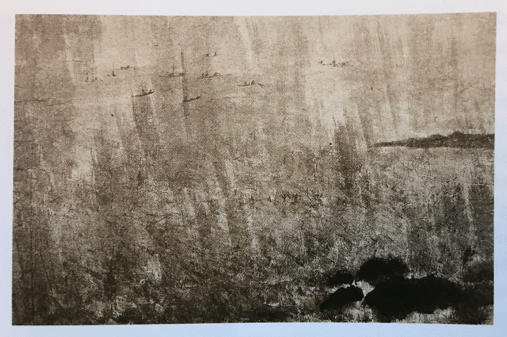

The same thing happened, eventually, with ink painting—which continued to explore realistic methods and contemporary subject matter while attending to the more painterly qualities of the medium. Figure painting gained popular prominence for possibly the first time in the medium’s Chinese history, due to “the need to promote positive role models of revolutionary behaviour”, ironically incorporating Romantic motifs from Western art history. Landscape, however, allowed artists to push the medium further than it had ever gone, moving into tonal abstraction as well as incorporating influences from other artistic media.

The dominant and politically endorsed style, however, was realism. And until 1978’s reform and opening-up, officially recognised and contracted artists operating in that vein could count on a wage and some form of often unrecognised public dissemination. But, afterwards, this system of political patronage faded (though it still exists in partial form today through provincial artist unions, where artists produce works that often require a morbid degree of connoisseurship to enjoy). New art was presented with what must have felt like the unprecedented choice of turning back to an aesthetic tradition (although the link to that tradition had been hacked so thoroughly at the root that only a rough approximation of official history remained); the choice of completely reinventing itself, as can be seen in much lively and idiosyncratic amateur painting from the period, as well as in the (better-known and well-documented) intentionally avant-garde work from the time, as in the works of Huang Yongping and Ai Weiwei; or the choice of using established realism to ironic effect—whether in critical realist works like Luo Zhongli’s “Father”, in “Scar” art which sought to uncover traumas, as in Cheng Conglin’s “Snow on a Certain Day and Month in 1968”, or in the photorealist-inspired works of Chen Danqing and Chen Yifei, which explored new subject matter and heightened the painterly stakes.

Much of what remains of Clark’s study documents the legacy of this exciting moment of experiments in form, including the return of Western modernism to the conversation. The book also chronicles the utter explosion of originality and creativity in the 1990s. This includes the blending of cultural stylings, as in Zhang Hongtu’s work, and the self-conscious mining of traditional techniques as modernist, as in Song Dong’s “writing” and “printing” works. It also emphasises the prominent role of performance art—simultaneously “realistic” and experimental in its emphasis on embodiment and endurance. Along the way it also more heavily discusses the influence not only of the global art market, which at the time could be read as having a heavy Western orientation, but also the importation of Western popular culture, and its influence on art. These influences also gave artists models for how to sell their work, and, if possible, make a living.

If this last bit has been discussed in many previous histories of Chinese art, Clark’s contribution to 1980s and 1990s historiography is to see it as on a continuum with non-mainland artists—from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and including those who reside in the West and whose cultural background is largely Western. These artists often participated in global art currents as they formed—as in the Californian Yun Gee’s Robert Delaunay-influenced “Man with a Pipe”. They also explored abstraction in the geographical Sinosphere outside of mainland China (which can be read as having dominated what is considered Chinese art for the entire twentieth century)—as in Hawaii-based artist Betty Ecke’s collage work. And experimentation came earlier as well—as in Taiwanese artist Tehching Hsieh’s performance work of the 1980s. By doing so, Clark loosens the frame of “Chinese art” from a single political or formal narrative, and instead refocuses on expansiveness as what it means to make Chinese art.

How to cite: Turner, Matt. “Experiments in Form: A Review of David Clark’s China-Art-Modernity.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 17 Sept. 2020, chajournal.blog/2020/09/17/china-art-modernity/.

Matt Turner is the author of the poetry collection Not Moving (2019) and the translator of Lu Xun’s collection of prose poetry Weeds (Seaweed Salad Editions, 2019). His essays and reviews can be found in Los Angeles Review of Books China Channel, Hyperallergic Weekend, Music & Literature, Cha, among other places. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife and co-translator, Haiying Weng. [All contributions by Matt Turner.]